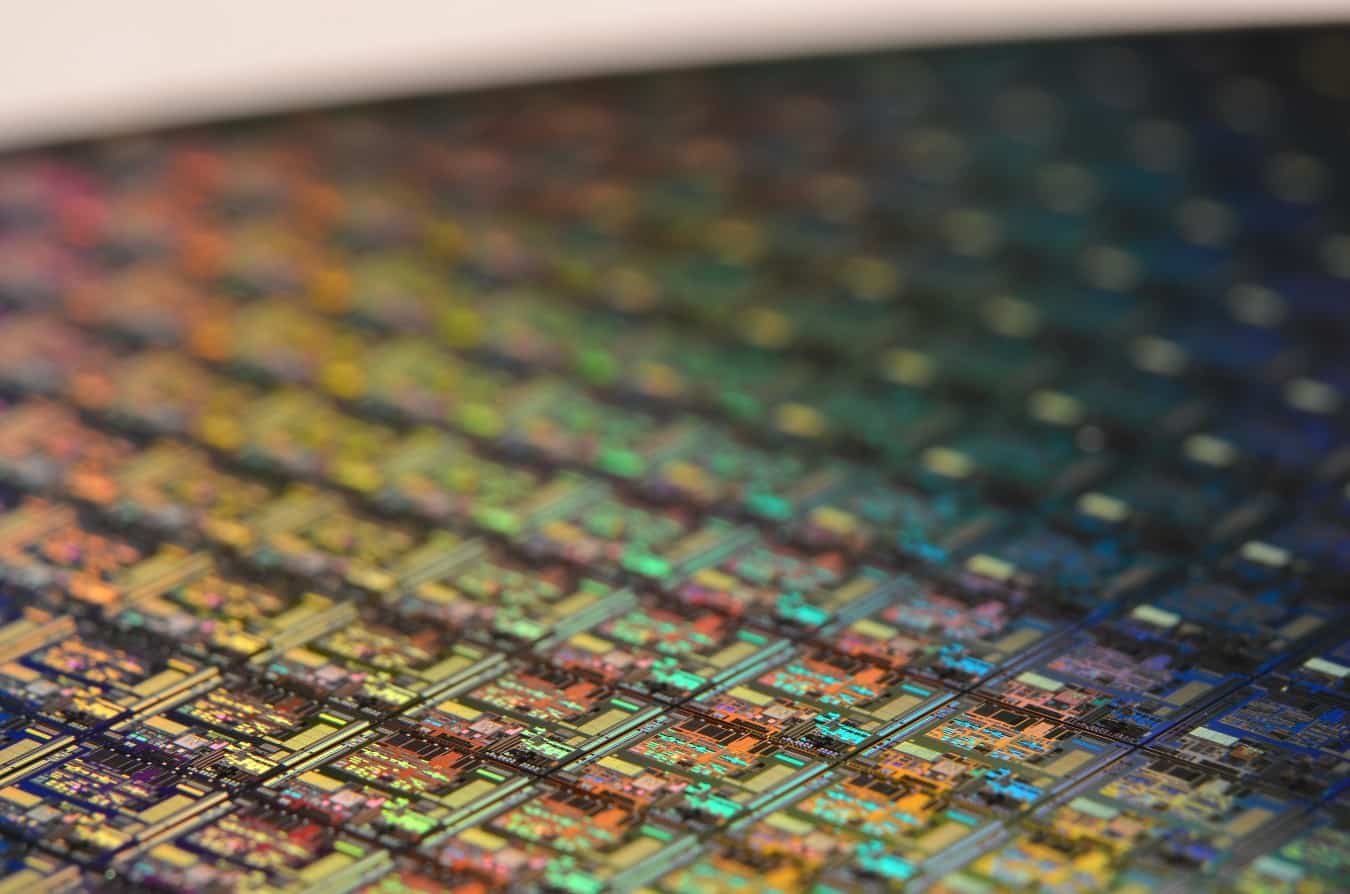

Photo by Laura Ockel on Unsplash

Hamza Mudassir, Cambridge Judge Business School

Chinese state-backed conglomerate Wingtech Technology is taking full control of the UK’s largest semiconductor foundry, Newport Wafer Fab (NWF), for £63 million. Wingtech has been a majority shareholder in NWF, which specialises in making chips for the car industry, since 2019 through its Dutch chip-maker subsidiary, Nexperia. But it is only now that the Chinese firm has decided to buy out all existing shareholders and debt-holders.

The news of the cross-border deal could not have come at a more uncertain time for the global semiconductor industry. The widespread shortage in this essential technological building block has led to very high second-hand prices for consumer electronics such as graphics processing units and video-game consoles. The US and China are being forced to deploy billions of dollars to build new semiconductor fabrication plants to ensure that the supply of valuable microchips does not dry up in future.

And while Wingtech has not attracted the same controversy as Huawei, its links to the Chinese Communist Party are deep enough. UK government ministers had indicated that they would not block the takeover of NWF, but such was the reaction from the Labour front bench and the media that Boris Johnson, the prime minister, has overruled them and ordered a national security probe.

But I believe his ministers were right in the first place. Newport Wafer Fab is neither strategically nor financially significant enough for the UK government to justify an intervention. Let me explain why.

A typical modern semiconductor foundry costs billions of dollars to build, and usually needs several years of production runs to achieve scale. This being the case, the paltry £63 million price tag for the Welsh-based plant sounds suspect at first glance. There has been speculation that the foundry was sold to the Chinese at an extraordinarily low price. But this could not be further from the truth.

Despite sky-rocketing demand for semiconductors, unnamed sources close to the NWF deal have reportedly indicated that the company has been struggling. A management buyout in 2017 ended up putting significant debt on the company balance sheet, including a £20 million loan from HSBC bank and an £17 million loan from the Welsh government.

High levels of debt tend to limit the ability of a company to invest in R&D and longer-term strategic projects, since the short-term pressure of paying back interest and principal leaves little cash for anything else. Such limitations quickly became a reality for the NWF management, which reportedly put up the company as collateral to win a contract and investment from Nexperia/Wingtech in 2019.

Fast forward to 2021, and the NWF management has reportedly been forced into selling to Wingtech for not meeting its contractual obligations. Such high-stakes dealmaking can partially explain why the value of NWF came out so low at a time when industry leaders like TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) have enjoyed multibillion dollar growth in valuations in the past few years. The NWF owners had reportedly called on the government to block the deal, only to be turned down.

Given the deeply technical nature of the semiconductor industry, you might think that every fabricator can produce chips for the latest iPhone. Far from it. Competitive pressures are steep and almost entirely innovation-driven, with most industry profits going to fabricators that can consistently reduce the size of the transistors they are manufacturing.

The smaller the transistors, the more of them can be packed into a single microchip. This allows for better performance while reducing power and heat requirements. Hence fabricators that can only produce older, larger transistors cannot command the same price premium as smaller ones, since most end users do not want bulky, hot, power-draining electronics.

For example, the popular Intel 486 processor, released back in 1989, was manufactured on a 1,000 nanometre (nm) process (this refers to the size of the smallest elements in the transistors on the processor – 1,000nm is one thousandth of a millimetre). The PlayStation 3’s powerful cell processor was manufactured on a 90nm one in 2006. By 2022, TSMC and Samsung will be manufacturing transistors on a 3nm process.

NWF is not in the same league, with its transistor manufacturing coming in at a coarser 180nm. This lack of competitiveness has resulted in the company focusing on producing transistors for low-margin power supplies for vehicles – which are neither technologically demanding nor as high margin as say 5nm+ AI chips like the ones being produced by Samsung for Tesla.

The UK government was right for not interfering in what are rudimentary market dynamics, where an inefficient player is being dismantled and dissolved into a larger company – Nexperia also makes chips in Hamburg and near Manchester. This takeover makes room in the market for more efficient players, and the probe by national security adviser Sir Stephen Lovegrove would do well to reach the same conclusion.

Critics of the deal should remember: just because a company makes semiconductors does not make it a national treasure. For this reason, NWF is just not important enough to have been bailed out with taxpayer money.

We asked Nexperia to comment on the takeover. A spokesperson said:

>Nexperia has had a very successful semiconductor fab in Manchester since the early 1970s. In close co-operation with the Welsh government, Nexperia has succeeded in preserving NWF’s operation, employment (500 jobs) and continuity at a time when NWF was about to financially collapse.

>Nexperia has repaid in full NWF’s £17 million debt to the Welsh government. It will bring its proprietary IP into NWF and will continue to invest and expand the plant. This will ensure NWF’s position as a key player in the Welsh Compound Semiconductor domain.

>Nexperia‘s goal is to make NWF as successful as its Manchester fab, and it is ready to work with the UK government to address any concerns regarding its involvement in the company.

Hamza Mudassir, Visiting Fellow in Strategy, Cambridge Judge Business School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.