Peter Martin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

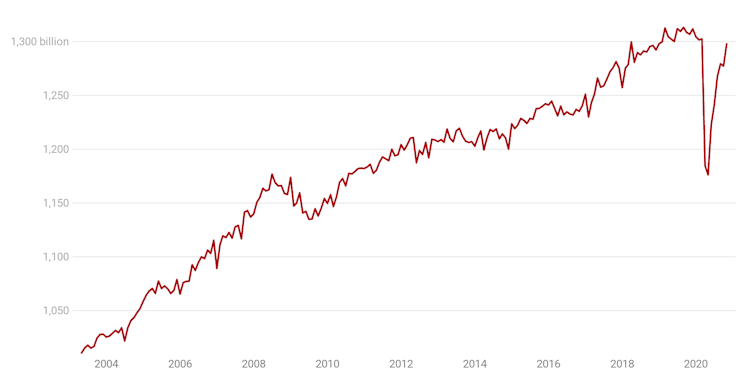

Outside of Victoria the number of hours worked has almost returned to where it was – nowhere near where it would have been, but almost where it was.

Employment figures released as Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was unveiling the mid-year budget update show 1,298 billion hours were worked outside of Victoria in November, just a whisker short of the 1,303 billion worked in March, before things went south.

On a graph it looks like a “V”, the much-talked about V-shaped recovery.

Monthly hours worked in all jobs, excluding Victoria

Eagle-eyed readers will note that hours worked were turning down before the coronavirus hit. They peaked in September last year.

Victoria itself has bounced back sharply from the lowpoint of its lockdown in August.

Then it put in 417 billion hours of paid work. In November, with its lockdown over, it put in 453 billion, not too far sort of its peak of 476 billion before things turned bad.

Frydenberg says 85% of the 1.3 million Australians who either lost their jobs or saw their working hours reduced to zero are back at work.

The numbers reflected in the so-called MYEFO budget update.

With more people back in jobs more quickly, and people leaving JobKeeper more quickly than expected in the October budget, the projected deficits will be somewhat smaller, peaking at just under A$200 billion this financial year instead of just over A$200 billion as expected in October.

The budget will still remain in deficit for as long as anyone can forecast, at least ten years, and even after that the government’s net debt will still exceed one third of gross domestic product, although falling interest rates will mean net interest payments start to fall before net debt does.

Some government loans cost it 5% to 5.75% per year in interest. As they expire in the next the years they will be replaced by loans costing 1% or less, and in some cases less than zero, where bidders for bonds offer negative interest rates.

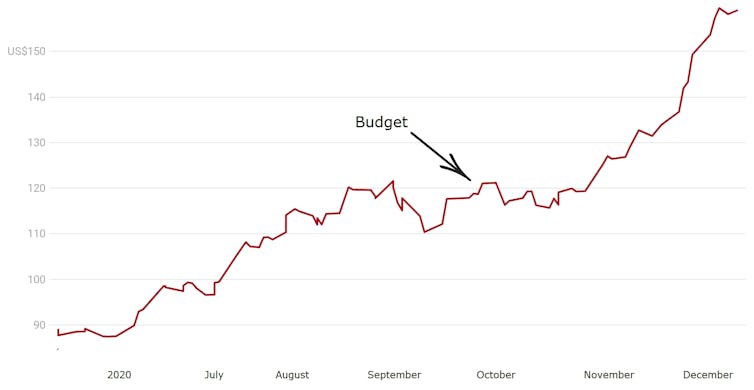

Soaring iron ore prices have pushed up estimates of this year’s company tax take from the $84.5 billion expected in October to $87.9 billion.

At the time of the budget on October 6, the “cost and freight” spot iron ore price (which includes the cost of getting to it to the buyer) was near US$120 a tonne. In the ten weeks since it has climbed to more than US$150 a tonne.

Spot iron ore price, US$ per tonne, cost and freight

The budget papers express the price differently, as a “free-on-board” price, which excludes shipping and is about US$10 less than the cost and freight price.

In what it says is a “prudent judgement”, the update expects the free-on-board price to glide down to US$55 a tonne by September 2021, meaning it expects it to more than halve.

Much depends on how quickly Brazil ramps up production after a series of catastrophic dam collapses and coronavirus interuptions.

The sooner it does, the sooner the price will halve and the volumes of Australian iron ore sold will wind back, cutting company tax revenue. China would rather buy from Brazil than Australia.

Boosting the budget is an improved forecast for employment. The unemployment rate is now expected to get down to 5.25% by June 2024, somewhat below the 5.5% expected at budget time.

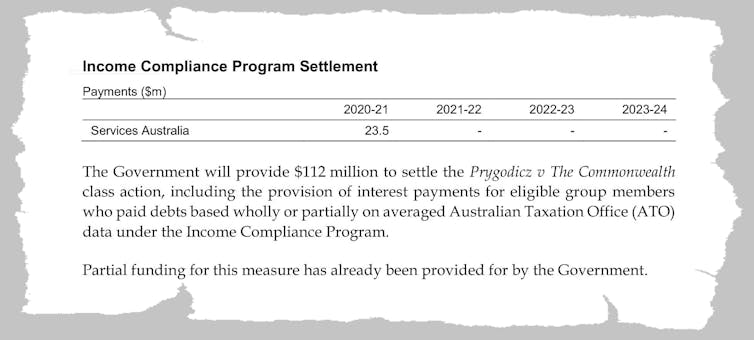

Working the other way is a self-inflicted injury. Tucked away in Appendix A of the update is confirmation of the cost of settling the case brought against the government on behalf of victims of Robodebt who were sent often-incorrect automatically-generated notices alleging that they had to pay back benefits.

It’ll cost $112 million, on top of the $705 million that’s been refunded.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.