Warwick Smith, University of Melbourne

Before the recession we were on a collision course with environmental disaster.

The recovery provides a rare opportunity to do things differently; to rebuild a better economy that can support living standards without irretrievably damaging the environment.

The closer we get to irreversible climate change, the harder that will become.

Doughnut economics, a concept principally developed by UK economist Kate Raworth, provides an intuitive way of thinking about it.

The ideas outlined in her book, subtitled Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, are increasingly being used around the world, including by a new collaboration Regen Melbourne, that’s looking at ways to making Melbourne a better, more socially-just and environmentally-responsible city.

The image to keep in mind is that of a doughnut, on the inside of which is economic and social freefall.

We need a certain amount of economic and social/political development to ensure everybody can live a good, healthy life with full social and political participation.

On the outside of the doughnut is an unsustainable impact on the environment.

The sweet spot, the “safe and just space for humanity” is, of course, in the doughnut itself. Mmm… doughnuts.

Conceptually it’s pretty straightforward. Practically, it is challenging.

Economics is traditionally defined as the study of the way societies allocate scarce resources. But in the modern world the reality is that, for rich countries such as Australia, there is no overall scarcity.

The challenge is to remain within the doughnut

Such countries have homeless and hungry people, for sure. But the also have enough resources, homes and food to provide for them. That they don’t is a question of distribution rather than scarcity.

In terms of the diagram, we already use enough resources to ensure nobody need be left in the hole on the inside of the doughnut. The danger is that we use too many resources and move beyond the outer edge of the doughnut into climate and ecological breakdown.

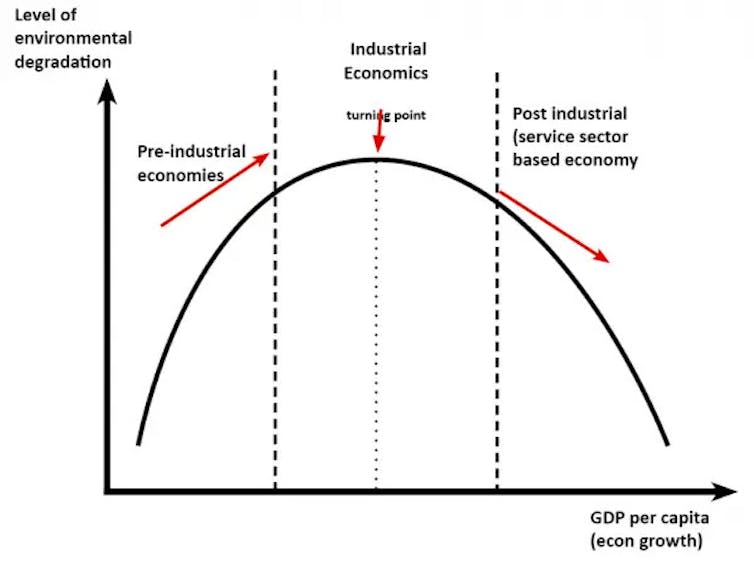

Here’s another diagram.

For quite some time amongst economists there’s been faith in what’s called the Environmental Kuznets Curve, where increasing consumption is said to lead to increased environmental degradation up to a point.

Beyond that point, as a society becomes post-industrial, extra consumption is said to lead to less environmental degradation as people become more environmentally conscious and use their wealth to buy different things – more services (such as yoga classes) and fewer goods (such as hamburgers).

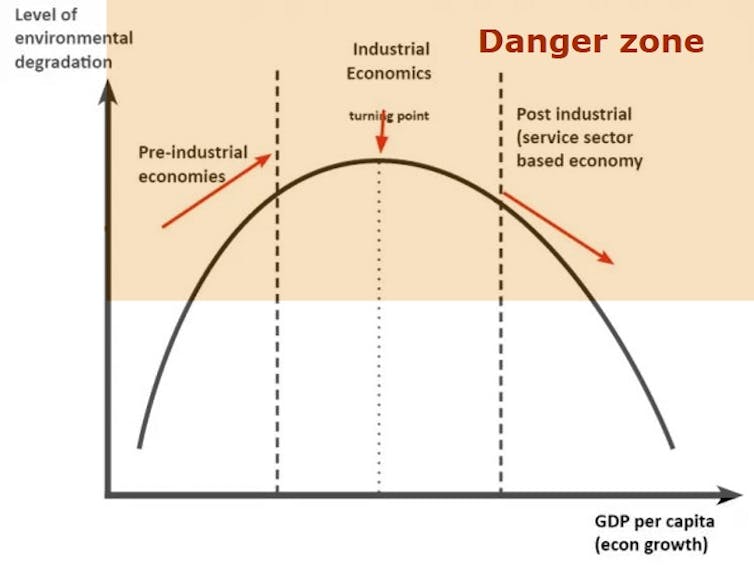

While the Environmental Kuznets Curve does indeed appear to be real, there is every indication that the global peak in environmental impact is far higher than the biosphere can withstand, which means a diagram like this:

We will need to bring the peak down, and that will be difficult for precisely the same reasons that people remain poor amid extraordinary wealth.

One is the capacity of deep-pocketed interests to influence regulators and governments to maximise profits. The other is the extent to which neoliberal economic thinking permeates social and political structures.

The modern neoliberal thinking tells us the best outcomes are achieved when markets are “free” without government “interference”.

Government attempts to tax, fine or charge for environmental damage are portrayed as interference, rather than protecting the environment.

This is easy because each individual hectare of vegetation that’s cleared doesn’t, by itself, do much damage to the environment, just as each tonne of carbon dioxide that’s released doesn’t do much damage to the climate.

It’s possible to introduce a carbon price or a carbon tax, but its easy to lobby against. Australia’s lasted two years, and governments are frightened to have another go.

The pandemic has expanded what’s possible

The pandemic has shown us that it’s possible to overcome that fear.

Environmental campaigner George Monbiot points out that for 10 years the number of people living – and dying – on Britain’s streets had climbed year by year. There wasn’t enough money to house them.

Then suddenly when the pandemic hit, and they were seen as potential carriers, the money could be found.

He says for decades government and industry had claimed that people would never give up international holidays and business flights. When humanity’s future was seen to be on the line, they did.

It was possible to embrace shift to “private sufficiency and public luxury”.

This is a challenge not only to economics but also to individual economists.

For better or worse, our discipline has a lot of power in the modern world and our views carry disproportionate weight.

We need the best of our economic minds helping us to build frameworks that will keep us in the doughnut. The future of our species depends on it.

Warwick Smith, Research economist, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.