Jane Simpson, Australian National University; Denise Angelo, Australian National University, and Francis Markham, Australian National University

Indigenous languages have been in the news this week. For the first time, an Indigenous language, Ngunnawal, was used for the acknowledgment of country at the opening of the ACT Legislative Assembly.

And two important reports have been released: the Closing the Gap Agreement and the National Indigenous Language Report (NILR) with linked qualitative research based on interviews and quantitative data reports.

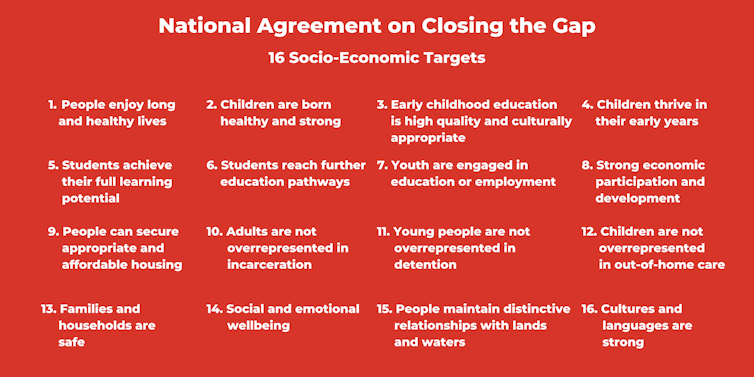

Both reports have Indigenous languages at their heart. The agreement lists “Cultures and languages are strong” as the last of 16 new socio-economic targets, and as one of five priority areas. NILR shows what is involved in achieving language targets – but also how Indigenous languages are involved in the other targets too.

The agreement promises:

By 2031, there is a sustained increase in number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.

We won’t know until implementation plans are released in 12 months’ time how government plans to do this, but action is urgently required given the threats faced by many traditional Indigenous languages.

The agreement co-design process, led by Indigenous peoples and organisations, has launched Indigenous cultures and languages into the centre of Indigenous public policy. Indigenous people have been demanding action to strengthen languages for years. We hope this new initiative will put an end to policies detrimental to Indigenous languages.

More than words

Stronger Indigenous languages are more than a standalone target. Every policy area needs to consider the language backgrounds of the people affected. No public policy is implemented in silence: speaking, listening, reading and/or writing are always needed for outcomes. So the language backgrounds of Indigenous people must be a prime consideration in the delivery of all policies.

The agreement makes cultural safety a high priority. NILR shows that linguistic safety underpins this. If you can’t receive information in the language you understand best, then you are not safe.

This is most obvious in emergencies, from extreme weather warnings to COVID-19 strategies, communicating instructions in languages people understand is fundamental. It matters just as much when visiting a doctor or attending school.

Tracking language data

The third National Indigenous Languages Report was released this week by the federal Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications. It contains results from a survey conducted in 2018-19 by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

NILR emphasises

building in recognition, respect and support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages across the policy lifecycle, from design, to implementation, to evaluation.

This goal requires high-quality information about the languages Indigenous people identify with, the languages they speak and the extent to which they speak them.

The agreement is a document filled with detailed data specifications, but is something of a “data desert” when it comes to Indigenous languages. And yet, this data matters a great deal to Indigenous people.

The language target is less precise than most of the other 15 socio-economic targets. It has no quantified goal, and instead prescribes a “sustained increase”.

The agreement identifies a significant need for “data development” around Indigenous language use, suggesting measures that would require research, development and substantial public funds. This need is strengthened by NILR.

On other measures, disaggregation – or teasing out the detail – is suggested for different geographic, economic and demographic groups. But this has not been suggested for different linguistic groups.

This level of detail is key. If we want services to be effective, service providers must know what languages people speak. Professional services, such as early childhood assessment or guidance for parents, can then be provided in the correct language(s), perhaps through an interpreter.

Bringing the data and targets together

NILR acknowledges the current reporting on Indigenous languages data is inadequate.

First, it explains that “Indigenous languages” are not a simple, one-size-fits-all idea.

There are hundreds of traditional Indigenous languages, spoken to varying extents, but the number of speakers is declining overall. There are new Indigenous languages recognised to varying extents, and the number of speakers is growing, as NILR shows.

In parts of Australia, people are learning their heritage Indigenous languages. In other parts, people are learning English as a “foreign language” (often with little support). Indigenous communities vary across Australia as to their “language ecologies”: which languages people are speaking, to what extent and in what situations.

NILR joins the dots about how languages fit together in Indigenous people’s lives – how they benefit from them, and how policy and services can do better by seeing the whole picture (or language ecology).

The approach helps policy makers and service providers more clearly see the roles different languages play in people’s lives. In generalised terms, one of three patterns emerges:

- places where Indigenous children mostly speak traditional Indigenous languages (and learn standard Australian English)

- places where Indigenous children mostly speak new Indigenous languages (and learn standard Australian English and their heritage languages)

- places where children speak varieties of English (and learn their heritage languages).

NILR and the associated research show how each language ecology might affect the other agreement targets. These include “early childhood education is high quality and culturally appropriate” and “social and emotional wellbeing”. Overall, qualitative research and quantitative research shows that speaking an Indigenous language and learning a heritage Indigenous language both have benefits for the well-being of their speakers. But language mismatches between Indigenous people and service providers are detrimental to well-being.

Policies and services are effective when they are attuned to people’s language backgrounds. Making languages strong requires tailored initiatives where communities are speaking Indigenous languages (traditional or new), learning them from older speakers or reviving them from archival material.

We look forward to an approach which brings the practical applications of NILR to help fulfil the aspirations of the agreement.

Jane Simpson, Chair of Indigenous Linguistics and Deputy Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, Australian National University; Denise Angelo, PhD Student, Australian National University, and Francis Markham, Research Fellow, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.