Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, University of Maryland

Rolling out a vaccine to stop the spread of a global pandemic doesn’t come cheap. Billions of dollars have been spent developing drugs and putting in place a program to get those drugs into people’s arms.

But amid an uneven distribution of vaccines – with poorer countries lagging far behind richer nations – another concern presents itself: the cost of not vaccinating everyone.

My colleagues and I sought to find out what the total hit to the global economy of uneven vaccination distribution might be.

To do so, we analyzed 35 industries – such as services and manufacturing – in 65 countries and examined how they were all linked economically in 2019, before the pandemic. For example, the construction sector in the U.S. relies on steel imported from Brazil, American auto manufacturers need glass and tires that come from countries in Asia, and so forth.

We then used data on COVID-19 infections for each country to demonstrate how the coronavirus crisis has disrupted global trade, curbing shipments of steel, glass and other exports to other countries. The more that a sector relies on people working in close proximity to produce goods, the more disruption there will be due to higher infections.

We then modeled how vaccinations could help to alleviate these economic costs, as a healthy and immune workforce is able to increase output.

Shouldering the burden

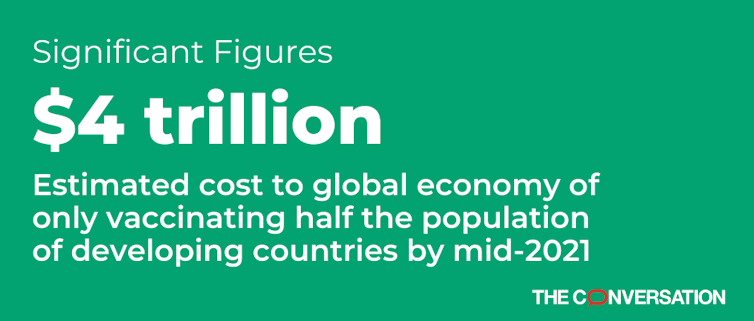

Our results showed that if wealthier nations are fully vaccinated by the middle of this year – a goal that many countries are striving for – yet developing countries manage to vaccinate only half of their populations, the global economic loss would amount to around US$4 trillion.

We estimated the global economic cost of developing countries not vaccinating any of their citizens to be around $9 trillion. Work is underway to increase the reach of vaccines to developing countries, but nonetheless, it is likely that poorer nations will still lag in total numbers vaccinated.

Whatever the toll is, the U.S., Canada, Europe and Japan would shoulder almost half the burden of continuing disruptions to global trade – even if they themselves managed to vaccinate the entirety of their own populations.

The findings come as the global community seeks ways to address the imbalance in national vaccinations. Results from our study, published as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research and its European counterpart, the Center for Economic Policy Research, were presented at a recent World Health Organization briefing. The timing of the report also coincides with President Joe Biden’s announcement that the United States intends to join COVAX – an initiative aimed at vaccinating at least 20% of the population of every country by the end of this year.

But COVAX is currently billions of dollars short of being able to meet that goal.

No economy is an island

Our research underscores that it is in rich countries’ direct economic interest to ensure poor nations are fully vaccinated as well.

Widespread vaccinations in wealthier nations will certainly help domestic businesses like restaurants, gyms and other services. But, industries such as auto, construction and retail that depend on outside countries for materials, parts and supplies will continue to suffer if vaccines are not made available worldwide.

No economy is an island – full global economic recovery will come only when every economy recovers from the pandemic.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Professor of Economics, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.