Juste Rajaonson, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and Georges A. Tanguay, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM)

International travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have prompted many travel enthusiasts to explore local and regional tourist destinations. However, communities have been affected very differently from increased numbers of homegrown tourists.

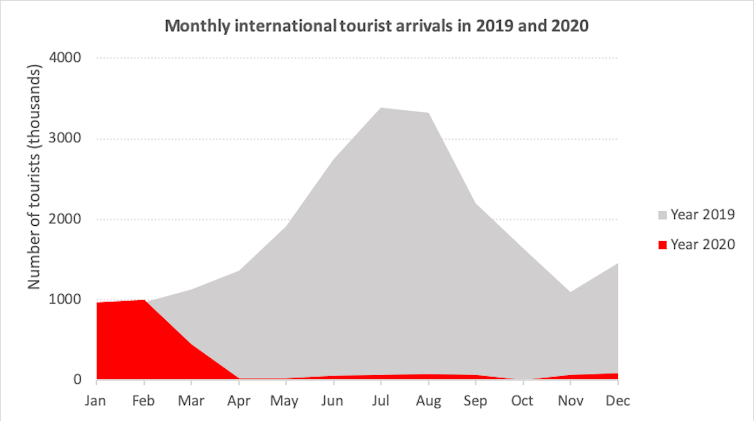

In Canada, the impact on international travel due to COVID-19 was immediate, with a decrease of 614,000 international arrivals to Canada in March 2020. That represented a 92-per-cent decrease over 2019 — a loss that has not yet been recovered.

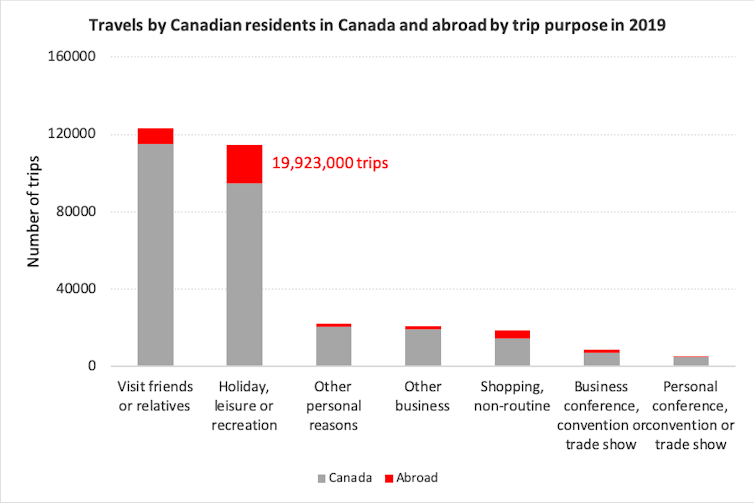

At the same time, travel restrictions played a role in shifting up to 20 million holiday and leisure trips abroad by Canadian residents to domestic destinations. Boosting domestic travel has been at the heart of federal and provincial government strategies to limit losses in the tourism sector.

The loss of international tourists

Canadians opting to visit domestic destinations over the past year have contributed to an increase in the share of domestic tourism in total tourism expenditures from 78.4 per cent in 2019 to 92.7 per cent in 2020. But trips made by Canadians in Canada only partially compensated for the losses associated with international tourists, as tourism spending in Canada fell by nearly 50 per cent in 2020 from 2019 levels.

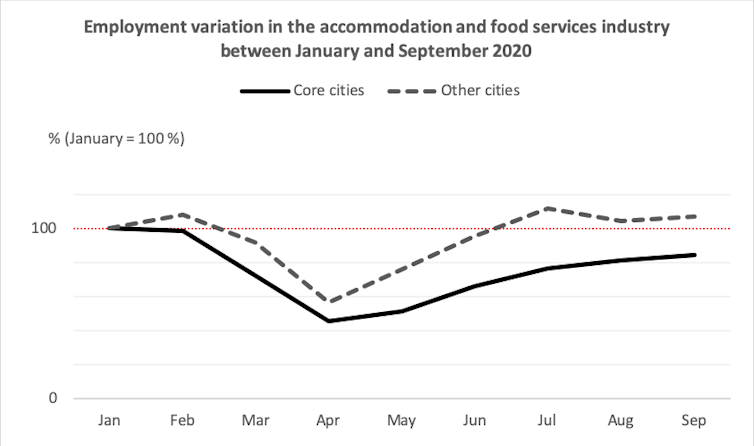

Not all destinations have been equally affected, however. There has been a variation in employment levels in the accommodation and food services sector in large Canadian cities like Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver compared to other small and mid-sized cities in 2020. Some of these municipalities are located on the fringes of larger cities, while others are in more remote areas.

Big cities versus regional destinations

The largest Canadian cities, which are usually major tourist destinations and gateways for international visitors, have experienced drastic declines in tourists and tourism spending.

For instance, Toronto lost $8.35 billion in 2020 due to the cancellations of many tourism activities related to events, festivals, conventions and business conferences. The number of international visitors to Montréal in 2020 decreased by 94 per cent over 2019, and the city experienced its lowest hotel occupancy rate ever of around 15 per cent. In Ottawa, hotel occupancy rates fell by 70 per cent during the pandemic, and the tourism sector lost almost half of the revenue generated in 2019.

In contrast, several destinations outside of major urban centres have benefited from the rise in domestic tourism to offset the loss of international tourists. However, not all of them have the same capacity to welcome visitors during the pandemic.

Some destinations had sufficient capacity in terms of space, accommodation and services. This was the case for many places close to large cities that offer outdoor activities and have been able to ensure adequate management of tourist flows.

In Canada, destinations such as Bromont in Québec and Rouge National Urban Park in Ontario, which both offer summer and winter outdoor activities, have implemented specific measures to cope with a high increase in demand reported by tourism operators.

The situation is similar elsewhere in the world, including in France, Belgium and Switzerland, where regional tourist destinations are attracting more travellers than big cities.

Some regional destinations in Canada have been overwhelmed by too many visitors, and they’ve struggled to accommodate them without affecting the environment and the quality of life of local residents.

The problems have included: significant increases of motorists, causing congestion and parking problems; so many visitors that it was difficult to follow preventive COVID-19 health measures; and the saturation of public places. In Canada, this has happened in the Gaspé and Rawdon in Québec and at Glen Morris, Grey Sauble, Niagara-on-the-Lake and the Northern Bruce Peninsula in Ontario.

Destinations in the United States, the United Kingdom, Scotland and France have also struggled with too many tourists.

How to manage tourists

With the next travel season upon us, governments can use various strategies tailored to the geographical trends of COVID-19 tourism.

Some government interventions have already been implemented, and it’s important they continue even with the end of the pandemic in view as vaccination efforts go into overdrive. That includes government financial assistance programs for tourism operators to help mitigate their income losses and enable them to continue to operate.

These programs are vital for metropolitan destinations like Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver, where the recorded economic losses have been the highest. The assistance has included wage support, rent subsidies and help in accessing credit.

Governments should also continue to support the promotion of domestic tourism for a greater number of destinations so that popular hotspots don’t become overcrowded. Additional measures should also be put in place to address the risk of an overflow of tourists in certain destinations as the pandemic continues.

With government support, cities should also develop strategies to establish acceptable limits on accommodations for tourists and visitors. Such measures would help preserve the environment and respect the quality of life of residents. This could mean, for example, establishing a limit on expanding parking lots in certain commercial sectors or on additional camping spaces near tourist attractions.

To be effective, such measures require monitoring and control, and laws and regulations must be enforced, including fines.

The popularity of some tourist destinations during the COVID-19 pandemic has brought economic opportunities to many communities. These tourist hotspots can seize upon those opportunities while respecting the need to control the number of visitors. Efficient management of tourist flows is critical, especially when several regions are aiming to attract permanent new residents and new businesses.

Juste Rajaonson, Professor of Urban Studies and Sustainability, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and Georges A. Tanguay, Professor of Urban Studies and Economics, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.