John Quiggin, The University of Queensland

When the coronavirus pandemic hit Australia in March 2020, the Morrison government took bold and imaginative action.

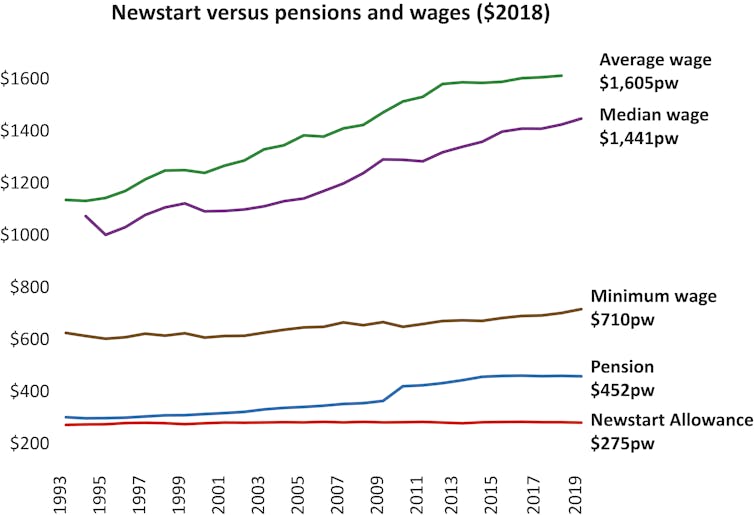

The most notable examples were its income support programs – JobKeeper, paying a A$750 weekly subsidy to employers to keep workers on the payroll, and JobSeeker, which doubled unemployment benefits relative to the Newstart allowance, frozen in real terms for nearly 30 years.

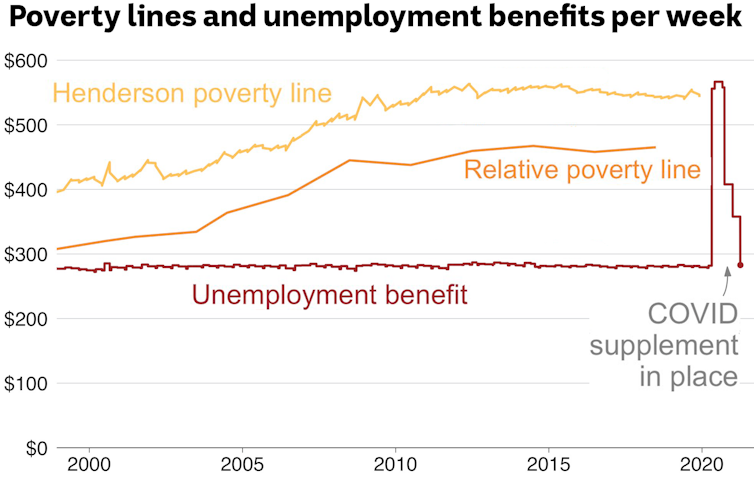

These measures were announced as temporary. The government has already begun winding them back as the economy recovers from the worst impacts of the pandemic. On January 1 the JobSeeker supplement (being paid to about 1.3 million Australians) was cut from A$250 to A$150 a fortnight. It will cease in March.

JobKeeper should end

There are good reasons to phase out JobKeeper. It was designed specifically to assist businesses forced to scale back their activities due to COVID-19 and the restrictions introduced to control it. Eligibility is, therefore, tied to the impact of the lockdowns that took place nationally in the first half of 2020, and again in Victoria from August to October.

With those emergency times behind us, many businesses have returned to something like business as usual, while some have closed for good. Others have been brave enough to start new businesses. JobKeeper isn’t relevant to any of these.

It has been partially replaced by JobMaker, a wage subsidy for employers intended to encourage the employment of younger workers, which is scheduled to be wound back in March and completely phased out by October.

The success of JobKeeper might lead to more consideration to temporary wage subsidies in response to future economic crises, perhaps along the lines of Germany’s Kurzarbeit scheme, which will run at least to the end of the year. But designing such a scheme would take a lot of time. Winding down JobKeeper in the meantime makes sense.

JobSeeker is another matter

The situation is very different with JobSeeker.

The inadequacy of the Newstart payment was widely recognised long before the pandemic. Organisations as disparate as the Australian Council of Social Service, the Business Council of Australia and the OECD have endorsed an increase. Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe has said raising Newstart said would do more for the economy than cutting taxes for high income earners.

The system of unemployment benefits in place before JobSeeker worked on the assumption there were jobs aplenty for anyone willing and able. Unemployment was seen as reflecting personal defects or, more charitably, a lack of particular skills needed for “job readiness”.

This assumption was clearly untrue even before the pandemic. As the long history of booms, busts and economic crises have shown us, all workers are vulnerable (some more than others) to losing their job through no fault of their own. The pandemic has reinforced that lesson.

The failure of Australia’s labour market to provide full employment is evident from high and increasing levels of underemployment, particularly among young people. Even before the the pandemic an unacceptably high proportion of workers struggled with stringing together part-time “gigs”.

Newstart is not enough

Returning to the poverty levels of the former Newstart allowance as Jobkeeper winds down is a terrible option. We should restore parity between unemployment benefits and other social security benefits such as the age pension.

Until the 1990s these benefits were roughly equal in value. Since then the age pension and similar benefits have been increased in line with average earnings. Unemployment benefits, however, have been frozen in real terms since 1994.

Compounding the increasing financial hardship, life for the unemployed has been made harder by the steady intensification of compliance and reporting requirements.

While the controversial “robodebt” scheme – in which many welfare recipients were hounded to repay money they did not owe – has been abandoned, more fundamental change is needed.

A liveable income guarantee

In an economy that cannot provide full-time work for everyone who wants it, we need to take a broader view of the way people can contribute.

To respond to the post-pandemic era, we should adopt the concept of a Liveable Income Guarantee (LIG).

The LIG is closely linked to the “participation income” proposed by British economist Anthony Atkinson. It starts from the principle that everyone has a right to a liveable income and the opportunity to contribute to society. It’s similar to a universal basic income but requires recipients to participate in socially useful activities.

The narrow measure of “formal employment” largely obscures the fact that many people without paid work productively contribute to society in other ways.

Unpaid work of parents, carers and volunteers has been estimated as equal to almost half of Australia’s GDP.

While the contributions of carers has been partly recognised through the Carer’s Payment, other forms of unpaid work have not.

What other contributions might be acknowledged under the LIG? There are many possibilities, most of which have some precedent but have not been considered as part of a comprehensive program of social participation, including volunteering, ecological care projects and artistic and creative activity.

As the year of JobSeeker and JobKeeper draws to a close, it’s time for the Morrison government to show some of the same boldness and imagination it had a year ago.

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.