Simon Bowen, Newcastle University and Alexander Wilson, Newcastle University

The Tyne and Wear Metro train fleet has served the UK’s busiest light rail network outside London for over 40 years. Now, these trains are at the end of their working life – and people across the region have been contributing to the design for their replacement.

In 2016, Nexus, the public body running the publicly owned Tyne and Wear Metro, applied for the funds to replace the trains and commissioned a public consultation to understand what people across the region wanted from their new trains.

Nexus were aware of our work at Newcastle University in collaborative research and design and asked us to run a more exploratory part of the consultation to complement the questionnaires, interviews and focus groups used elsewhere.

Doing design with people – also known as co-design – has two benefits. It satisfies people’s democratic right to influence what affects them, and results in designs that better fit those people’s needs.

This is the case for the new Tyne and Wear Metro trains, which are set to be built by manufacturer Stadler. The design for the new trains was based on the concerns and ideas from the over 3,000 people who took part in the 2016 consultation. It includes more wheelchair spaces and CCTV cameras, information screens throughout, a sliding step between trains and platforms and multipurpose spaces for bikes, buggies and luggage.

Bringing people in

We began by running a series of co-design workshops with people who had a variety of needs – such as commuters, people with disabilities, and people travelling with bicycles. We also ran pop-up labs: drop-in activities in busy public locations spread across the region, such as shopping centres, travel interchanges, and a local market.

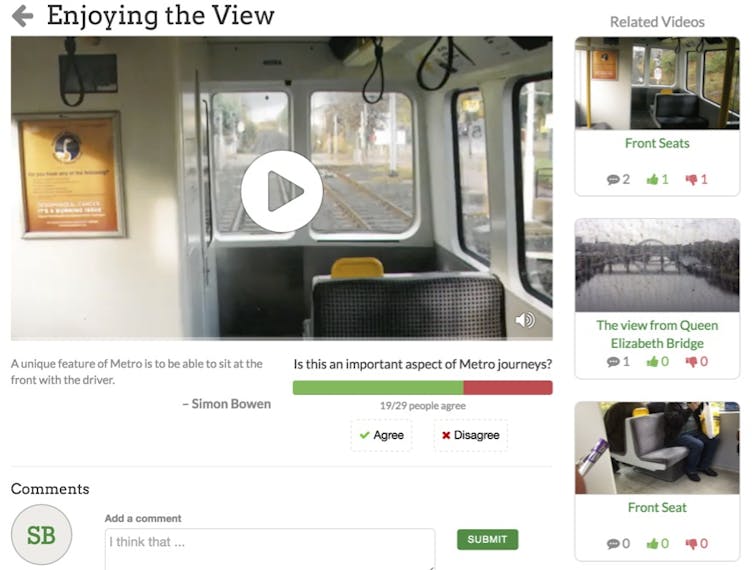

We asked workshop participants to record their experiences of the metro trains. These video clips were shared between the workshop participants to work out common concerns with the current trains. The clips were also featured on our website and at pop-up labs to gather further comments and to generate discussion.

We noticed that the participants’ ideas tended to focus on fixing concerns rather than exploring new design possibilities. So, we produced some imaginative design ideas that suggested alternative ways of dealing with concerns, such as tackling anti-social behaviour on trains by crowd-sourcing the monitoring of onboard CCTV cameras.

This enabled people to explore the implications of these ideas. For example, participants discussed how this management of onboard CCTV might be misused by some to show off to the cameras.

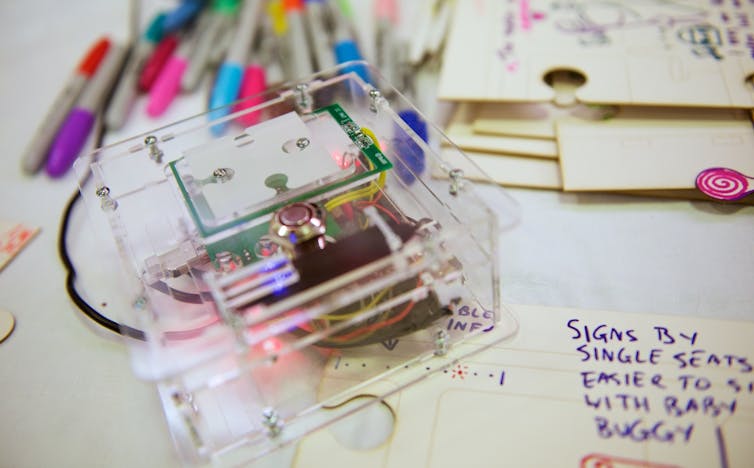

The pop-up labs were an opportunity to undertake quick, less detailed activities with more people across the region. The participants used technology we have developed, called JigsAudio, to share their experiences and ideas. People wrote and drew answers to a topic on wooden or card puzzle pieces. Each puzzle piece had its own unique electronic tag, and the participants held the piece to the JigsAudio device to record audio descriptions linked to their drawings.

This allowed people to share their ideas in ways they were used to (drawing, writing, and talking) rather than concentrating on how to use a new technology. This approach gave people more time to think about their answers.

We also produced videos that illustrated concerns with current trains and ideas for the new trains. Videos were shown to pop-up lab and website visitors, who fed back if they agreed or disagreed with them and left text or audio and video comments. This allowed our workshop findings to be developed further with more people across the region.

New findings

Our findings complemented the other parts of the 2016 consultation. They reinforced common concerns and added participants’ descriptions of how these issues made them feel and their suggestions for dealing with these concerns. For instance, crowded trains made people feel claustrophobic, and they suggested train occupancy sensors as a solution.

Second, they showed how train designers needed to consider several viewpoints, not just the most popular. For example, sideways seating was preferred overall, but our participants found this suitable for shorter journeys and preferred front or back facing seating for longer journeys.

Third, having an open approach revealed new findings. For example, rather than focusing on the interior of the trains, as other parts of the consultation did, our workshop participants recorded getting on and off trains, and discussed safety concerns about the gaps between trains and platforms and ideas to reduce them. https://www.youtube.com/embed/8EAjwSKgxpo?wmode=transparent&start=0

In 2020, after Stadler’s proposed designs were received, Nexus asked us to run another public consultation to find whether the new design fitted public needs and help decide on interior design options. The 2020 consultation received an unprecedented 23,000 public responses.

The new Tyne and Wear Metro trains’ journey towards reality is a powerful example of the value of carrying out co-design, both at scale and online.

Simon Bowen, Senior Research Associate in the School of Computing, Newcastle University and Alexander Wilson, ESRC Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.