John Hawkins, University of Canberra; Jinjing Li, University of Canberra; Michael James Walsh, University of Canberra; Riyana (Mira) Miranti, University of Canberra; Xiaodong Gong, University of Canberra, and Yogi Vidyattama, University of Canberra

The Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (known as the LMITO or “lamington”) has been given yet another new lease of life.

What started in 2018 as a stop-gap until broader tax cuts were introduced, was extended because of COVID after the tax cuts were introduced in the 2020 budget and has now been extended again in 2021 to assist with the COVID recovery.

Which is odd, because, being a delayed payment (it is only paid out as tax refunds after the end of each financial year), it offers anything but real-time support.

And despite its name, it isn’t offered to Australians on very low incomes.

If you earn less than the A$18,200 tax-free threshold, LMITO gives you nothing.

If you earn more than that and up to $37,000 it will cut your tax by up to $255.

The LMITO gradually increases with income until it reaches $1,080 for taxable incomes between $48,000 and $90,000.

Beyond $90,000 it starts falling and cuts out entirely for taxable income over $126,000.

The quick fix that came to stay

It was introduced by the Government in the 2018 budget as a temporary measure until the ‘stage 2’ tax cuts came in from 2022. In the 2020 budget the Government brought forward the ‘stage 2’ tax cuts. This meant the LMITO was no longer needed for its original purpose, but the Government extended it for a year.

In the budget, the treasurer labelled the extension a “new and additional tax cut”.

Others might see it as continuing to escape a tax increase.

The extended LMITO will be received by about 10 million taxpayers from July 1 2021 after they lodge their tax returns. The extension will cost $7.8 billion.

This cost makes it one of the more expensive decisions announced in the budget, and — especially if it gets extended again, it will as good as destroy the promise in earlier budgets of a simpler, flatter tax schedule.

Here’s what it does to tax

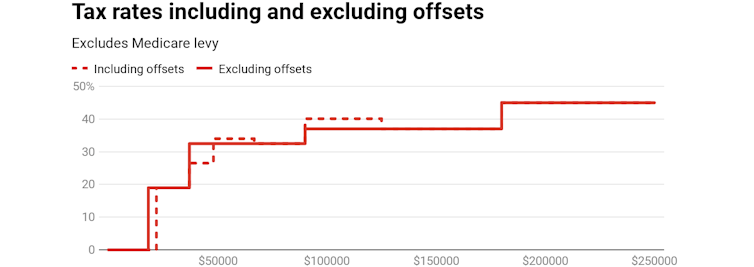

The LMITO (and its sibling, the longstanding Low Income Tax Offset) make the tax schedule more complicated.

Ignoring them, there are four marginal tax rates, soon to be three after the Morrison government’s stage three tax cuts are introduced.

Including them, as this graph prepared by Steven Hamilton for The Conversation in 2019 shows, there are many more marginal rates which fall and rise and fall and rise again.

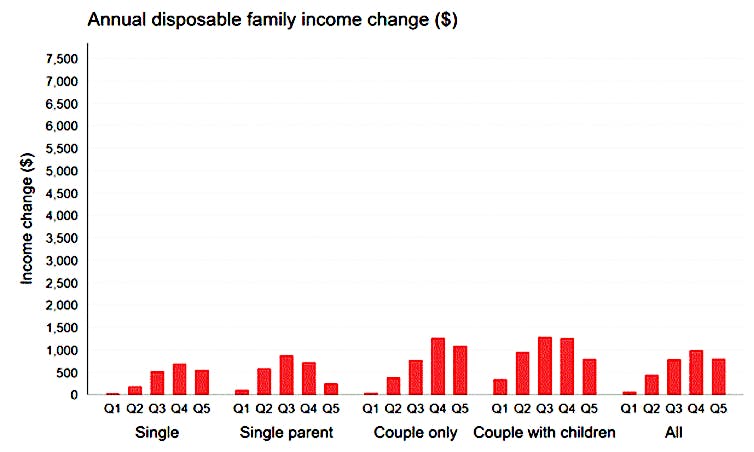

Our calculations using the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling’s STINMOD+ model suggest the LMITO could be more accurately called the “medium and high income tax offset”.

In the following charts the ‘“Q1” columns refer to the poorest fifth of households and “Q5” to the fifth with the highest incomes.

The largest benefits from LMITO accrue to households in the middle.

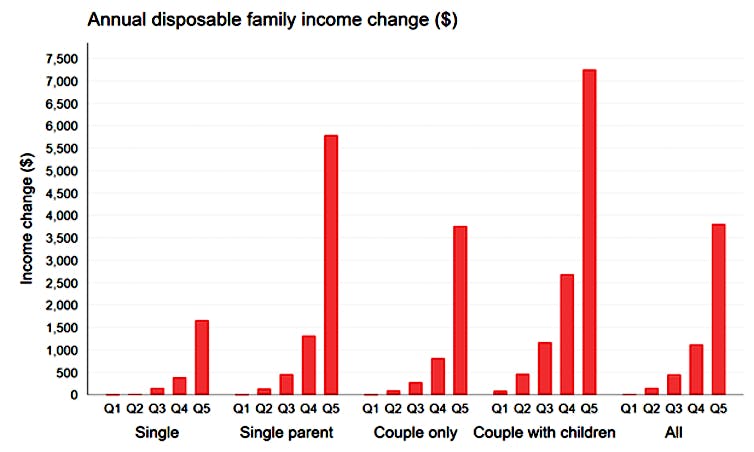

The impact of LMITO is very small compared to the planned stage three cuts, due to arrive in 2024-25.

Our graph drawn on the same scale shows they are extraordinarily highly skewed towards high income earners.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg called the LMITO extension “a stimulus measure that will support the recovery”. But it is astoundingly poorly suited for this purpose.

Timely stimulus deferred

The extra year of LMITO won’t be paid until July 2022, at the earliest, depending on when people submit their 2021-22 tax returns.

By then the economy ought to be well over a year out of recession.

Worse still, in the view of economists including Nobel winner Richard Thaler, lump-sum payments such as LMITO are more likely to be saved than would be cuts in ongoing tax that lifted fortnightly pay.

A much better stimulus would have been to have kept in place the boost to JobSeeker payments delivered by the coronavirus supplement and removed at the end of March this year. Almost all of the people on it spent it.

Extending LMITO enables the treasurer to escape the political opprobrium that would come from being seen to increase middle class taxes.

But it runs the risk of making permanent a poorly-designed stop-gap that neither delivers money to the people who need it most nor delivers economic stimulus when it is needed.

John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society and NATSEM, University of Canberra; Jinjing Li, Professor, NATSEM, University of Canberra; Michael James Walsh, Associate Professor, University of Canberra; Riyana (Mira) Miranti, Associate Professor & Convenor of BGL Indonesia Program, University of Canberra; Xiaodong Gong, Associate professor, University of Canberra, and Yogi Vidyattama, Senior Research Fellow in Social and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.