Michael Toole, Burnet Institute

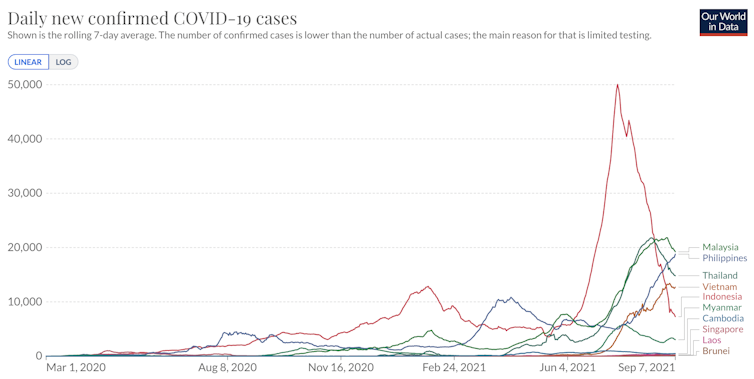

Since May, the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has spread rapidly through most of Southeast Asia.

Of the ten member nations of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), all but Brunei have experienced recent surges, most of which have seen the highest number of cases since the pandemic began. However, these nine countries have experienced different COVID-19 trends.

Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam reported very low daily cases throughout 2020 but are all now experiencing record surges in cases. Vietnam and Thailand are reporting 13,000-14,000 cases daily.

Singapore had a huge first wave in early 2020, reaching 1,000 cases a day, mainly affecting migrant workers. The country has now fully vaccinated 79% of its entire population but is currently experiencing a spike in new cases.

Myanmar had a surge in late 2020 and a lethal second wave this July, and cases are once again increasing.

The three outliers that have struggled throughout most of the pandemic are Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. Indonesia’s massive third wave is now in steep decline but more than 80,000 deaths have occurred since early June.

Malaysia began to report an increase in cases in September 2020, which led to a peak in February and then to a huge ongoing third wave.

It’s now the Philippines that is cause for most concern in the region. The country has reported more than two million cases and 34,000 deaths. The daily case rate is the second highest in Southeast Asia, after Malaysia.

The Philippines’ fourth wave

The Philippines has experienced four waves of COVID-19. The first wave was modest, reaching a peak seven-day rolling average of 316 in early April 2020.

From early June 2020, cases began to steadily increase leading into the second wave, which reached a peak of around 4,300 daily cases in late August.

The third wave reached a peak of 11,000 average daily cases in mid-April 2021.

However, it is the fourth wave, fuelled by the Delta variant, which is the most severe since the pandemic began and shows no sign of slowing. By September 8, the daily average had reached almost 19,000 cases.

How has the Philippines responded?

The Philippines government imposed strict restrictions early in the pandemic. In mid-March 2020, President Rodrigo Duterte ordered Metro Manila and adjacent provinces to be put under “enhanced community quarantine” (ECQ).

Under ECQ, mass gatherings were prohibited, government employees worked from home, school and university classes were suspended, only essential businesses stayed open, mass transportation was restricted, and people were ordered to observe social distancing.

When ECQ was imposed on March 15, the country had reported just 140 cases and 12 deaths. Despite the restrictions, the totals reached 5,453 cases and 349 deaths one month later.

The government relied heavily on the police and military to ensure all health protocols were followed. This led critics to denounce its militarist approach. Some civic groups providing assistance to communities faced harassment and attacks.

Others criticised the government for taking a war-like approach that focused on identifying and punishing those who breached the rules rather than working cooperatively with, and providing financial support to, affected communities.

The term “pasaway”, a Filipino word referring to a stubborn person, became a punitive target in government communications. Amid the lockdown, the term pasaway referred to people violating government-imposed health protocols.

At the end of May 2020, restrictions were gradually loosened, entailing the re-introduction of mass transportation and the opening of government offices and certain businesses. At this time, the average had risen to 578 daily cases, the highest since the pandemic began.

The easing of restrictions was driven by economic factors – the unemployment rate had risen to 17.7% and 26% of businesses had closed.

Amid the gradual easing of quarantine restrictions, the Philippines saw an accelerating increase of COVID-19 cases. By the end of July, 75% of beds in intensive care units, 82% of isolation beds and 85% of ward beds in Metro Manila were occupied.

The fourth lockdown

Fast forward to early August 2021 as daily cases surged past 8,000. A new lockdown was announced in the National Capital District, which comprises more than half the country’s economy.

By August 20, Manila and surrounding provinces had been in either ECQ (enhanced community quarantine) or modified community quarantine for a total of 170 days since the beginning of the pandemic.

On that day, restrictions were eased even as daily cases surged to a record high of 17,231 and 317 deaths. More than 26% of samples tested positive, the country’s highest positivity rate so far.

The Philippines is trying desperately to spur activity in an economy that contracted a record 9.5% last year.

However, this risks having the health system totally overwhelmed. Many hospitals fear a mass exodus of nurses who are overworked, underpaid and constantly exposed to the virus. Filipino nurses are paid the lowest salaries among nurses in Southeast Asia.

What’s needed now?

The response by the Philippines has often been among the strictest in the world. However, the imposition and lifting of restrictions have not always been based on the caseload. The easing of restrictions has been driven by a desire for economic revival.

With only 14% of the population fully vaccinated and case numbers continuing to soar, the country is unlikely to vaccinate itself out of this outbreak before the health system is overwhelmed.

With cases now occurring in all 17 provinces, a clear national “vaccine plus” policy needs to be urgently implemented to save both lives and livelihoods.

This means while accelerating the vaccine rollout, there also need to be other preventive measures, such as mask wearing, physical distancing, attention to indoor ventilation, an effective test-trace-isolate system and, when necessary, localised lockdowns.

Michael Toole, Professor of International Health, Burnet Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.