Choon Key Chekar, Lancaster University; Joshua R Moon, University of Sussex, and Michael Hopkins, University of Sussex

According to the recent House of Commons report on the UK’s pandemic response, one of the government’s key failings was to assume that the success of countries like South Korea in controlling the virus couldn’t be replicated in Britain. This decision to ignore approaches that were proving successful elsewhere was one of the UK’s biggest oversights early in the pandemic.

However, the report itself falls into a similar trap. It regards South Korea’s pandemic response as exceptional due to its advanced use of digital technology, ignoring the fact that the country also relied a lot on old-fashioned social interventions – contact tracing, quarantine and isolating cases – aided by boots on the ground.

To combat COVID and future pandemics, governments need to heed the lessons of these social interventions and not just the technological ones. South Korea teaches us that high-tech solutions can help protect against disease, but these work together with social interventions – interventions that the UK has not used as effectively.

What a world-beating system looks like

The UK government had the ambition of creating a “world-beating” test-trace-isolate system. Yet the House of Commons report concludes that England’s system has produced little effect, despite great expense. Other countries too have not been able to contain COVID sufficiently without resorting to draconian lockdowns. However, South Korea has been regularly cited as an exception.

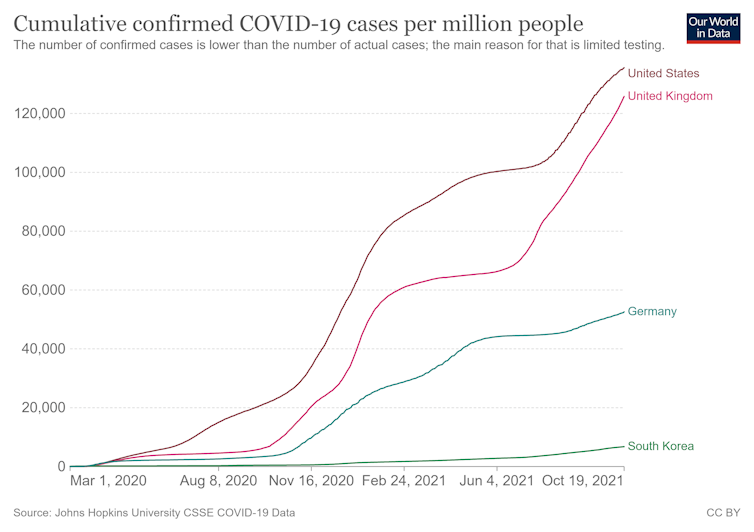

While South Korea has had to introduce some control measures to limit the spread of the virus – there have been curfews for businesses and limits on the size of gatherings in 2021 – it has avoided full lockdowns and border closures while keeping cumulative confirmed COVID cases relatively low. It’s worth remembering that South Korea is one of the world’s most densely populated large countries.

Key to this has been quarantine measures for travellers arriving in the country, which were introduced very swiftly, and the country’s highly effective test-trace-isolate system. This carefully designed process provides local support for those in isolation, while monitoring them and sanctioning non-compliance.

Yes, mobile phone data and other forms of surveillance have been used to trace people who might have the virus. But once a positive case is confirmed, it is human intervention that ensures those people don’t spread the virus further.

A case officer from the local council is assigned to work with affected households. They communicate with infected people throughout the self-isolation period. After initially making contact over the phone to inform people of the need to self-isolate and the guidelines to follow, case officers then deliver a stay-at-home kit as discreetly as possible to protect the person’s privacy.

This local council-funded kit contains essentials that prevent the person from needing to go out. They receive food, drink, bin liners, a thermometer for monitoring their condition, and face masks and hand sanitiser to help prevent further infection. Kits can also be tailored, for instance, to include certain foods or medications – and even pet food.

The case officer is the infected person’s primary point of contact, providing advice and support over the 14 days of self-isolation. Again, technology plays a role here. A smartphone app can be used by the case officer to monitor the person’s self-reported symptoms and to make sure (via GPS) they aren’t breaking quarantine. But its influence shouldn’t be overstated. The app is mandatory, but those who don’t own a smartphone are still able to get support via phone calls and text messages.

People self-isolating can contact their case worker when extra support is needed, for instance, with urgent daily business such as banking or pet care. Because the relationship works both ways, this encourages compliance through the creation of a social bond. The comprehensive and individualised support given to those isolating primarily ensures compliance by removing barriers rather than punishing infractions.

The need to address the loss of income that self-isolating people face was also identified early on, with modest payments of up to $US374 (£270) made easily available.

The effectiveness of these interventions is clear: published data suggests non-compliance with self-isolation rules has been extremely low in South Korea throughout the pandemic. Those who do break the rules risk losing the financial support that the government provides.

Not breaking the rules has also been encouraged as a social norm through daily reporting in the media on the number of people not adhering to isolation. Generally, this is no more than four people a day – in a country of 55 million.

Lessons as yet unlearned

The South Korean experience reveals just how effective locally delivered and individually tailored self-isolation systems can be. But rather than seeking to replicate South Korean success, politicians, experts and the media in the west have repeatedly suggested that this performance is based on intrusive data-surveillance techniques enabled by a compliant national culture that cannot be replicated in their countries.

The House of Commons report suggests that if the UK were to try to emulate South Korea, the lessons to be learned concern the use of high-tech surveillance systems and comprehensive digital contact tracing. This misses out many of the core elements of South Korea’s pandemic response that help make sure people isolate and quarantine as needed.

Focusing on technologies to adopt in the future ignores the more immediately transferable lessons on how to break chains of infection in a fast-moving pandemic. It is about time we acknowledged that comprehensive, “shoe-leather” public health systems should be the bedrock of containing current and future disease outbreaks. Much of what has worked in South Korea is exceptional only in that other countries – such as the UK – have made no effort to replicate it.

Choon Key Chekar, Senior Research Associate, Division of Health Research, Lancaster University; Joshua R Moon, Research Fellow, Science Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex, and Michael Hopkins, Senior Lecturer, University of Sussex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.