Stephen Kirchner, University of Sydney

The outgoing Trump administration presided over one of the most dramatic tightenings in US immigration policy since the 1930s.

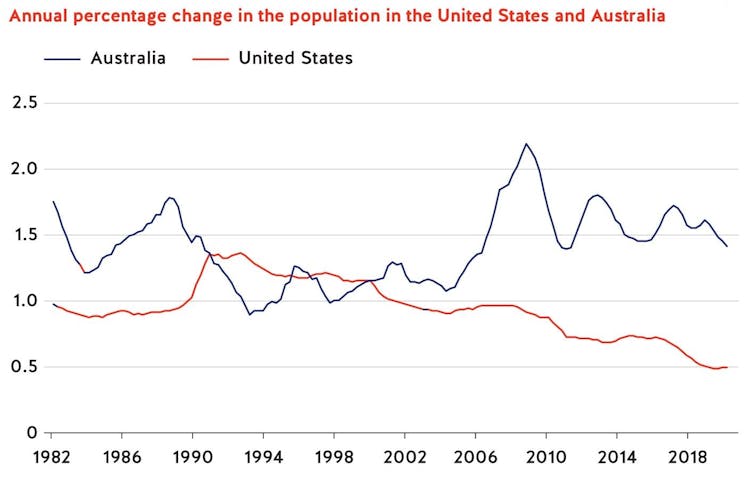

Along with declining fertility, this saw US population growth fall to its lowest rate in a century, even before the onset of the pandemic.

Compared to its peak in the 1990s, the contribution of net migration to growth in the US working age population fell by 60% between 2010 and 2018.

While the incoming Biden Administration is expected to take a more relaxed approach, Trump’s legacy will be difficult to quickly or fully unwind.

Coming to America

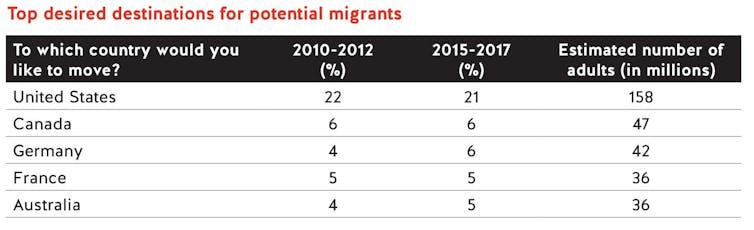

The US has traditionally been the preferred destination for migrants. It normally gets close to half of the skilled migrants who come to OECD countries and around one third of skilled migrants globally.

Combined, the English-speaking nations of the US, Canada, the UK and Australia typically capture around 70% of skilled migration flows.

Immigration has historically been a key source of US national power and a leading driver of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Earlier this year, President Trump suspended new work visas, barring tens of thousands of foreign workers and their dependants from entering, and preventing US companies from hiring in two of the skilled visa categories.

According to a Brookings Institution study, that single order wiped US$100 billion from the market value of US firms, highlighting the extent to which they rely on skilled foreign workers.

Previous studies have found that the arbitrary cap on skilled visas (which was 190,000 and had tightened to 65,000) only served to increase offshoring as US firms hired foreign contractors rather than bringing them on shore.

The work visas executive order was just one of around 400 Trump used to tighten immigration policy.

Going to Australia?

Australia is potentially a close substitute for the US on the part of prospective migrants. It typically ranks just below the US, Canada and Germany as their preferred destination.

Trump’s actions give Australia the opportunity to capture some of the global talent that would have normally gone the US but has been increasingly turned away by its increasingly restrictive approach.

Australia’s international arrivals are currently capped by limited isolation and quarantine capacity.

Even Australian citizens are finding it difficulty to return.

The government is assuming that Australia will suffer net outflows in 2020-21 and 2021-22, the first time net overseas migration has turned negative since 1946.

Including births and deaths, total population growth is expected to fall to just 0.2% in 2020-21, the lowest since the first world war.

Perhaps more disturbingly, the Australian government is assuming no future adjustments to make up for the losses — neither a return to the previous levels of net overseas migration over the projection period, “due to economic uncertainty and softer labour market conditions” nor accelerated migration beyond that to get back what was lost.

Australia will be left with less population and productive potential than it would have had there been no pandemic. But it needn’t.

Ramp up capacity, change policy

In my new United States Studies Centre report released this morning, I argue Australia can get back what it has lost, in part by taking migrants the US won’t.

The government’s immediate priority should be to fund an increase in managed isolation and quarantine capacity to ramp up our ability to take in migrants.

In the long-term, it should set aside its current annual cap of 160,000 on permanent migration.

The cap won’t matter much for the next few years because it is unlikely to be filled, but it will in future years, denying Australia the ability to get back what it has lost.

As Australia’s economy recovers, skilled workers are going to become scarce.

Experience with Australia’s uncapped temporary skilled visa program shows skilled migration increases the wages of local workers and induces them to specialise in occupations requiring communication and cognitive skills.

Employers are required to pay foreign workers a minimum salary equal to at least that of comparable local workers.

Hong Kong is shaping up to be a good source of skilled foreign workers. The Australian government has already relaxed visa arrangements for Hong Kong but mainly for temporary migrants.

Australia faces competition. Canada is looking to take up to one million skilled migrants through to 2022 — about 350,000 per year.

Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.