This year’s Closing the Gap report tells a more positive story than the 2017 report on the seven measurable gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in the areas of health, education and employment.

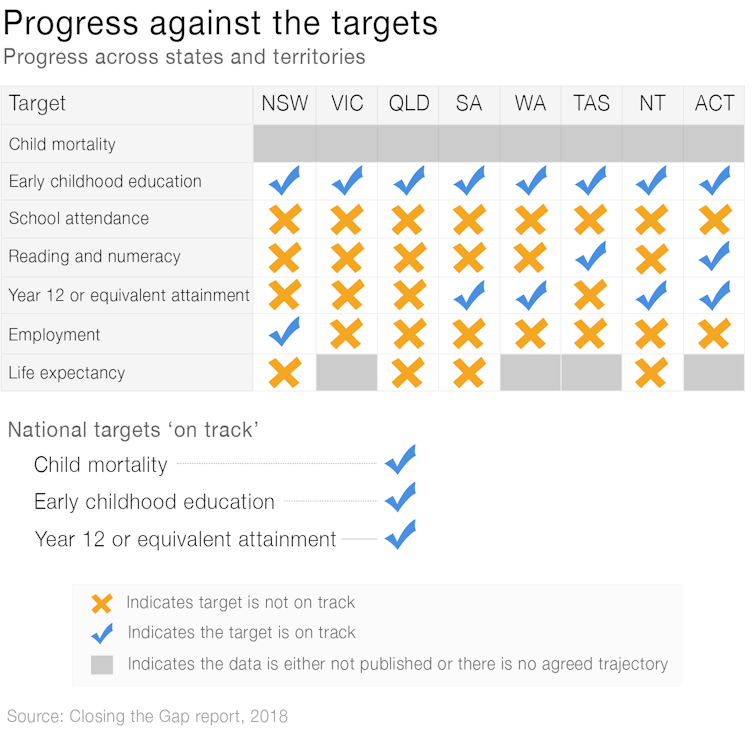

According to the government’s figures, the targets relating to Year 12 attainment, early childhood education, and child mortality are on track to be closed. In last year’s report, Year 12 attainment was on track, but child mortality wasn’t. Early childhood education is a revised target, and 2018 is the first time trends can be monitored. The previous early childhood target was not met.

But the targets related to life expectancy, employment, literacy and numeracy, and school attendance are not on track to being met.

There has been steady improvement in absolute terms on most of the measures over the last decade, even if gaps have not closed at the desired pace.

Despite the symbolic importance these targets have gained and their precise numerical definition, progress toward meeting them remains remarkably hard to measure. This can lead to confusion and a sense that data is being constructed or interpreted to fit prior assumptions.

Low numbers of child deaths in a given year mean child mortality figures fluctuate across years in a way that doesn’t reflect real change. So, the child mortality target was on track, then it wasn’t, and now it is again. Policy parameters, however, haven’t changed much over the period.

For early childhood education, the number of Indigenous children attending preschool and the total number of eligible children come from different data sources. As those sources are revised (for example with new population estimates), it can look like rates are higher or lower than they actually are.

Care needs to be taken in interpreting progress, and ascribing this to actual policy change.

Three reasons why gaps aren’t closing

Given its inability to meet such precisely defined targets, the Closing the Gap policy has been widely described as a failure. There are at least three important reasons why this is so.

First, laudable policy ambition was not matched with a radical change in how business is done in Indigenous affairs.

It has been clear since 2008 there would be little prospect of closing gaps in health and employment within a generation if business-as-usual policymaking continued. That same analysis showed closing the gap in educational attainment was more realistic if trends predating Closing the Gap continued. The latest report has vindicated this forecast.

However, without significant changes to how Indigenous policy was made, funded, and implemented, it seems the Closing the Gap policy was always destined to fail.

Second, governments’ stated policy goals have not always matched their policy actions.

An example of the mismatch between words and deeds can be found in employment policy. The abolition of a key job creation program – the Community Development Employment Projects scheme – has led to declining employment rates in remote parts of Australia. This reform has stalled progress toward closing employment gaps, not assisted it.

Closing the Gap has also been hampered by competing policy priorities, such as the attempts to eliminate the federal budget deficit. It is likely the repeated cuts to the Indigenous affairs budget – especially in 2014 but also more recently with the apparent shortfall in the remote housing funding – has hobbled potential progress.

Similarly, evidence suggests one of the most significant Indigenous policy initiatives in recent years – the Northern Territory Intervention – may have directly widened health and school attendance gaps.

These negative outcomes are worse still when the opportunity costs of the immense amount of money and policy attention devoted to the Intervention are considered. As well as disempowering Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory, the Intervention cost time and money that could have been better spent elsewhere.

Third, measures intended to achieve the targets have rarely been subject to careful evaluation and revision. Evaluations when they do occur rarely capture causal impact. And they often don’t capture the voices of those who were affected by the policy.

While there has been much talk from successive governments about the importance of evidence-based policy in Indigenous affairs, the promised focus on high-quality policy evaluation has yet to materialise.

Most importantly, the Closing the Gap framework has never tackled head-on the most important gap of all: the gulf between the political autonomy and economic resources of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Arguably, the framing of Closing the Gap as a technical problem – reported on with a barrage of statistics, targets, measurement discussions and the like – serves to hide the extent to which Indigenous disadvantage is a political problem requiring structural reforms.

The apparent sidelining of reforms that Indigenous people have long argued would help to close gaps should lead us to question whether depoliticisation is the Closing the Gap policy’s real “target”.

![]() There has been little in the Closing the Gap agenda that has empowered Indigenous people to implement local solutions to the issues that they identify as being problems. If the promised “refresh” of Closing the Gap does not put resources – and the power to direct them – into Indigenous hands, the prospects for closing socioeconomic gaps are likely to remain distant.

There has been little in the Closing the Gap agenda that has empowered Indigenous people to implement local solutions to the issues that they identify as being problems. If the promised “refresh” of Closing the Gap does not put resources – and the power to direct them – into Indigenous hands, the prospects for closing socioeconomic gaps are likely to remain distant.

______________________________________

By Francis Markham, Research Fellow, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University and Nicholas Biddle, Associate Professor, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

TOP IMAGE: The targets relating to Year 12 attainment, preschool enrolment, and childhood mortality are on track to be closed, according to the 2018 Closing the Gap report. (AAP/Marianna Massey/TheConversation)