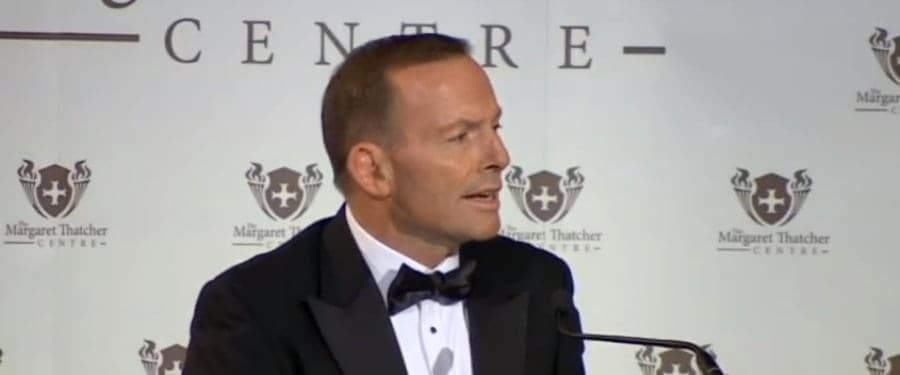

Full transcript of speech given by former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott for the 2015 Margaret Thatcher Lecture in London. Also view the full speech in the video, above.

____________________

I am both honoured and humbled to give this lecture in memory of Margaret Thatcher, who revived the ‘great’ in Great Britain and whose leadership was the gold standard to which so many others have subsequently aspired. But unlike you, we have at least solved one of the wicked problems now afflicting Europe: we have secured our own borders

She was, indeed, the longest serving British prime minister since Walpole; but she was so much more than just an election-winner. A ‘mind-the-shop’ conservative she most emphatically was not. She didn’t just respond to events; she shaped them; and, in so doing, she changed Britain and she changed the world.

It’s true that the world she helped to create: of rising prosperity almost everywhere driven by freer markets; of declining international tension under benign American leadership; and of increasing democratic pluralism inspired by the collapse of communism, now seems a fading dream – but we, her admirers, are here to improve things not to lament them.

Obviously, the defeat of Stephen Harper’s government in Canada is a bitter blow – but he changed his country for the better and he proved that conservatives can win elections not once but three times running.

In this audience, some may be disappointed that my own prime ministership in Australia lasted two years after removing Labor from office – but as Lord Melbourne is supposed to have said: “to be the Queen’s first minister (even) for three months is a damn fine thing”.

Set against the decisive victory of the Cameron government here, helped by Lynton Crosby, and John Key’s third straight win in New Zealand, recent developments are hardly the eclipse of conservatism, more the ebb and flow of politics.

The lesson of Margaret Thatcher’s life is that strong leaders can make a difference; that what’s impossible today may be almost inevitable tomorrow; and that optimism is always justified while good people are prepared to “have a go”, as we say in Australia.

I was a student, at Oxford, at the time of the Falklands War. I recall the shock Britons felt at the Argentine invasion and their visceral determination to reverse it. I remember thrilling to Enoch Powell’s parliamentary admonition that, by her response, the “iron lady’s” true mettle would soon be judged – because I sensed that she would not let us down.

And I now know, courtesy of Charles Moore’s splendid biography, how the response could so easily have been hand-wringing and impotent appeals to the United Nations had Mrs T not seized upon a military plan brought to her by a relatively junior officer.

That was the essence of her greatness: on the things that mattered, she refused to believe that nothing could be done and would work relentlessly to set things right. She believed in Britain – in its history, in its institutions and in its values – and, by acting on her beliefs, she helped others to believe as well.

She refused to accept the post-war consensus that Britain’s great days were over. She instinctively rejected government-knows-best approaches to running the economy and to managing society. And she was convinced that the world was more likely to prosper if Britain was a serious country with a global role rather than just another province in the united states of Europe. She inherited a Britain that was in rapid economic and strategic decline; and left it the most dynamic economy in Europe, and the United States’ principal global ally.

On Soviet missiles aimed at Europe, she didn’t see nuclear annihilation to be averted at all cost but an evil empire to be shown that aggression would not pay. On the Falklands, she did not see an Argentine grievance to be negotiated but a monstrous violation of British sovereignty. On council houses, she did not see a government service but a neglected asset that would better be looked after by owner-occupiers taking pride in their own homes.

She didn’t see unions protecting workers so much as bullying their employers into bankruptcy. She didn’t see state-owned enterprises as “national champions” so much as an endless burden on taxpayers.

There was a moral dimension and an intellectual clarity that made her a hero to liberal-conservatives everywhere, rather than simply another successful politician. To Thatcher, the prime ministership wasn’t about holding office; it was about getting things done. It wasn’t about achieving consensus; it was about doing the right thing.

It’s usually presumptuous to invoke the glorious dead in support of current policy – but your invitation to give this lecture suggests there was at least a hint of Thatcher about my government in Australia: stopping the flow of illegal immigrant boats because a country that can’t control its borders starts to lose control of itself; the repeal of the carbon tax that was socialism masquerading as environmentalism; budget repair so that within five years, the Australian government will once again be living within its means; the free trade agreements with our biggest markets to increase competition and make it fairer; the royal commission into corrupt union bosses; an even stronger alliance with the United States and a readiness to call out Russia for the shooting down of a civilian airliner.

But, like all driven people, Margaret Thatcher was more interested in the next problem than the last one. Today, we best honour her life and legacy by bringing the same tough-mindedness to the problems of our time that she brought to the problems of hers.

Parliamentary democracy and the rule of law; “freedom broadening slowly down from precedent to precedent”; the notion of civilisation as a trust between the living, the dead and the yet-to-be-born: this was the heritage she’d been elected to preserve and strengthen.

Her focus, were she still with us, would be the things of most consequence: managing the nation-changing, culture-shifting population transfers now impacting on Europe; winning the fight in Syria and Iraq which is helping to drive them; and asserting Western civilisation against the challenge of militant Islam.

Naturally, the safety and prosperity that exists almost uniquely in Western countries is an irresistible magnet. These blessings are not the accidents of history but the product of values painstakingly discerned and refined, and of practices carefully cultivated and reinforced over hundreds of years.

Implicitly or explicitly, the imperative to “love your neighbour as you love yourself” is at the heart of every Western polity. It expresses itself in laws protecting workers, in strong social security safety nets, and in the readiness to take in refugees. It’s what makes us decent and humane countries as well as prosperous ones, but – right now – this wholesome instinct is leading much of Europe into catastrophic error.

All countries that say “anyone who gets here can stay here” are now in peril, given the scale of the population movements that are starting to be seen. There are tens – perhaps hundreds – of millions of people, living in poverty and danger who might readily seek to enter a Western country if the opportunity is there.

Who could blame them? Yet no country or continent can open its borders to all comers without fundamentally weakening itself. This is the risk that the countries of Europe now run through misguided altruism.

On a somewhat smaller scale, Australia has faced the same predicament and overcome it. The first wave of illegal arrivals to Australia peaked at 4000 people a year, back in 2001, before the Howard government first stopped the boats: by processing illegal arrivals offshore; by denying them permanent residency; and in a handful of cases, by turning illegal immigrant boats back to Indonesia.

The second wave of illegal boat people was running at the rate of 50,000 a year – and rising fast – by July 2013, when the Rudd government belatedly reversed its opposition to offshore processing; and then my government started turning boats around, even using orange lifeboats when people smugglers deliberately scuttled their vessels.

It’s now 18 months since a single illegal boat has made it to Australia. The immigration detention centres have-all-but-closed; budget costs peaking at $4 billion a year have ended; and – best of all – there are no more deaths at sea. That’s why stopping the boats and restoring border security is the only truly compassionate thing to do.

Because Australia once more has secure borders and because it’s the Australian government rather than people smugglers that now controls our refugee intake, there was massive public support for my government’s decision, just last month, to resettle 12,000 members of persecuted minorities from the Syrian conflict – per capita, the biggest resettlement contribution that any country has made.

Now, while prime minister, I was loath to give public advice to other countries whose situations are different; but because people smuggling is a global problem, and because Australia is the only country that has successfully defeated it – twice, under conservative governments – our experience should be studied.

In Europe, as with Australia, people claiming asylum – invariably – have crossed not one border but many; and are no longer fleeing in fear but are contracting in hope with people smugglers. However desperate, almost by definition, they are economic migrants because they had already escaped persecution when they decided to move again.

Our moral obligation is to receive people fleeing for their lives. It’s not to provide permanent residency to anyone and everyone who would rather live in a prosperous Western country than their own. That’s why the countries of Europe, while absolutely obliged to support the countries neighbouring the Syrian conflict, are more-than-entitled to control their borders against those who are no longer fleeing a conflict but seeking a better life.

This means turning boats around, for people coming by sea. It means denying entry at the border, for people with no legal right to come; and it means establishing camps for people who currently have nowhere to go.

It will require some force; it will require massive logistics and expense; it will gnaw at our consciences – yet it is the only way to prevent a tide of humanity surging through Europe and quite possibly changing it forever.

We are rediscovering the hard way that justice tempered by mercy is an exacting ideal as too much mercy for some necessarily undermines justice for all.

The Australian experience proves that the only way to dissuade people seeking to come from afar is not to let them in. Working with other countries and with international agencies is important but the only way to stop people trying to gain entry is firmly and unambiguously to deny it – out of the moral duty to protect one’s own people and to stamp out people smuggling.

So it’s good that Europe has now deployed naval vessels to intercept people smuggling boats in the Mediterranean – but as long as they’re taking passengers aboard rather than turning boats around and sending them back, it’s a facilitator rather than a deterrent.

Some years ago, before the Syrian conflict escalated; extended into Iraq; and metastasised into the ungoverned spaces of Libya, Yemen, Nigeria and Afghanistan, I got into trouble for urging caution in a fight that was “baddies versus baddies”.

Now that a quarter of a million people have been killed, seven million people are internally displaced and four million people are destitute outside its borders and considering coming to Europe, the Syrian conflict is too big and too ramifying not to be everyone’s problem.

The rise of Daesh has turned it into a fight between bad and worse: the Assad regime whose brutality is the Islamic State death cult’s chief local recruiter; and a caliphate seeking to export its apocalyptic version of Islam right around the world.

Given the sheer scale of the horror unfolding in Syria, Iraq and everywhere Daesh gains a foothold – the beheadings, the crucifixions, the mass executions, the hurling off high buildings, the sexual slavery – and its perverse allure across the globe, it’s striking how little has been done to address this problem at its source.

The United States and its allies, including Britain and Australia, have launched airstrikes against this would-be terrorist empire. We’ve helped to contain its advance in Iraq but we haven’t defeated it because it can’t be defeated without more effective local forces on the ground.

Everyone should recoil from an escalating air campaign, perhaps with Western special forces on the ground as well as trainers, in a part of the world that’s such a witches’ brew of danger and complexity and where nothing ever has a happy ending – yet as Margaret Thatcher so clearly understood over the Falklands: those that won’t use decisive force, where needed, end up being dictated to by those who will.

Of course, no American or British or Australian parent should face bereavement in a fight far away – but what is the alternative? Leaving anywhere, even Syria, to the collective determination of Russia, Iran and Daesh should be too horrible to contemplate.

That’s why it’s a pity that the recent UN leaders’ week summit was solely about countering violent extremism – which everyone agrees involves working with Muslim communities – and not about dealing much more effectively with the caliphate that’s now the most potent inspiration for it.

Of course, the challenge of militant Islam needs more than a military solution – but people do have to be protected against potential genocide. Of course, you can’t arrest your way to social harmony – but home grown terrorism does need a strong security response. Of course, the overwhelming majority of Muslims don’t support terrorism – but many still think that death should be the punishment for apostasy. Of course, the true meaning of Islam is a matter for Muslims to resolve – but everyone has a duty to support and protect those decent, humane Muslims who accept cultural diversity.

Looking around the globe, it’s many years since problems have seemed so daunting and solutions less clear. Yet the worse the times and the higher the stakes, the less matters can be left in the too hard basket. More than ever, Western countries need the self-confidence to stand up for ourselves and for the universal decencies of mankind lest the world rapidly become a much worse place.

Like the countries of Europe, Australia struggles to come to terms with the local terrorism that Daesh has inspired. Like you, we are trying to contain Daesh from the air while waiting for a Syrian strategy to emerge. But unlike you, we have at least solved one of the wicked problems now afflicting Europe: we have secured our own borders.

All of us, then, must ponder Margaret Thatcher’s example while we wait to see who might claim her mantle. Good values, clear analysis, and a do-able plan, in our day as in hers, are the essentials of the strong leadership the world needs.