Alert systems need to be clear and easy for everyone to understand. Yet, to date, the UK’s national alert system has created confusion and been largely ignored.

Now, a second local alert level system has been introduced in England. I’m not convinced it will do any better. Other countries, from New Zealand to Vietnam to South Africa, have developed and used alert level systems effectively in the management of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. So why is the British government struggling?

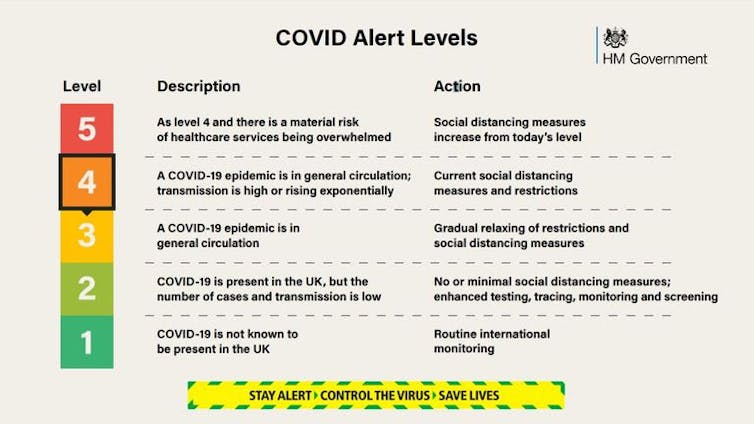

The first national COVID-19 alert system was introduced in May, comprising five levels. Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland initially wanted their own systems, but have since adopted the same system, with some minor variances. Initially, the UK was set at alert level four, reduced to level three on June 19, and raised to level four again on September 22, presumably when SAGE was arguing for a national lockdown to “break the circuit” following the re-opening of schools and universities.

In May I set out seven key reasons why this alert level systems would fail, many of which have transpired. Changes to the alert level are decided by the all-important R number: the average amount of people a single infected person will pass the disease on to. But it’s proven difficult to accurately establish the R number, and it’s unclear exactly how decisions to reset the alert level are made. All of this is unlikely to change going forwards.

The national alert level also fails to reflect the need for, and subsequent introduction of, stricter local restrictions in specific areas. The value of this national system is further limited given that the levels do not correlate with specific social distancing rules.

It also seems very hard – perhaps even impossible – for the public to find out what the national COVID-19 alert level is. It’s not on the dedicated government coronavirus webpage. This is in stark contrast to other nations like South Africa and New Zealand, where the alert level system is clearly displayed online, the current level highlighted, and the relevant risks and rules for each level displayed in a unified and consistent manner that is reinforced across the nation from a single source.

These issues are somewhat addressed by the new local COVID-19 alert level system. But is it enough to work?

Accommodating the local

On October 12, Boris Johnson announced that COVID-19 “figures are flashing at us like dashboard warnings on a passenger jet”. After eight months of significant levels of confusion, due to non-standard, changing information that has been haphazardly presented, the answer to the flashing lights, it seems, is to introduce an entirely new local COVID-19 alert level system.

Comprising three tiers that, according to the government, will “simplify and standardise local rules”, it’s three levels are set at medium, high and very high. By developing a simpler and standardised system that can be locally adapted, the chances of confusion will be reduced and will help provide a clearer message tied to specific rules, a key requirement of any warning or alert.

Yet local restrictions need to be tied to the bigger picture. And as social distancing rules are different in each nation, there has long been confusion for those that live near national borders or those travelling. As the new local alerts are only applicable in England, standardisation remains limited in use over the UK and across the borders. We need a system that can accommodate local and national needs. This is possible, but demands a clever design.

Alerts are a powerful tool

The government is moving in the direction that other nations use for their alert levels: they have created a website that will tell you your local alert level restrictions, and are issuing some useful graphics that do address prior concerns around clarity and transparency. This is positive. But there is still confusion and fragmentation amongst the public and tensions between local leaders and central government over what tier to assign.

As an expert in alert level systems, I’m not convinced that this new local system will be enough to offset previous failures. There was no mention of the national COVID alert level systems in the recent announcement, so it is not clear how these two systems work together, or if the broader system is now defunct. Why is the UK government continually revising and changing its alert systems? Why is this information still not clear and transparent?

UK chief medical officer Prof Chris Whitty has said he is “very confident” the new three tier alerts will slow the spread of coronavirus. But he also stated that even the toughest measures under the new rules “may not be enough to get on top of it”.

The new local alert system can’t last long: it is not designed to incorporate all levels of risk severity and it doesn’t include a fourth tier of “low risk”. This demonstrates that the system is purely responsive, designed for the moment, not for representing all possible scenarios in a clear and standardised manner that would enable people to be prepared.

A distinct lack of expertise from emergency management or civil protection experts is showing loud and clear. The UK has the expertise to do this, so why isn’t it happening?

By acting now to deal with those “flashing dashboard warnings” rather than preparing ahead, these COVID-19 alerts are unlikely to fulfil their potential to help navigate the nation through a challenging winter. The UK deserves more.

Carina J Fearnley, Associate Professor in Science and Technology Studies, Director of the UCL Warning Research Centre, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.