Erin Baker, University of Massachusetts Amherst and Matthew Lackner, University of Massachusetts Amherst

The United States’ offshore wind industry is tiny, with just seven wind turbines operating off Rhode Island and Virginia. The few attempts to build large-scale wind farms like Europe’s have run into long delays, but that may be about to change.

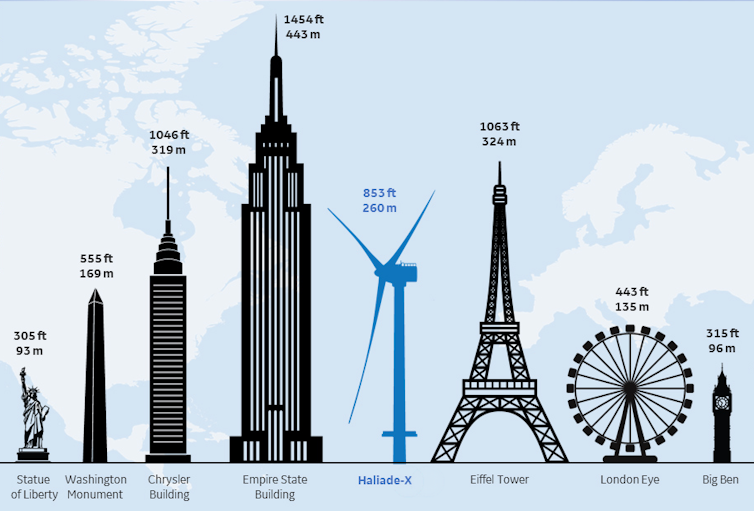

On May 11, 2021, the U.S. government issued the final federal approval for the Vineyard Wind project, a utility-scale wind farm that has been over a decade in the planning. The wind farm’s developers plan to install 62 giant turbines in the Atlantic Ocean about 15 miles off Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, with enough capacity to power 400,000 homes with clean energy.

The project is the first approved since the Biden administration announced a goal in March to develop 30,000 megawatts of offshore wind capacity this decade and promised to accelerate the federal review process. To put that goal in perspective, the U.S. has just 42 megawatts today. Vineyard Wind expects to add 800 megawatts in 2023.

So, are we finally seeing the launch of a thriving offshore wind industry in the North America?

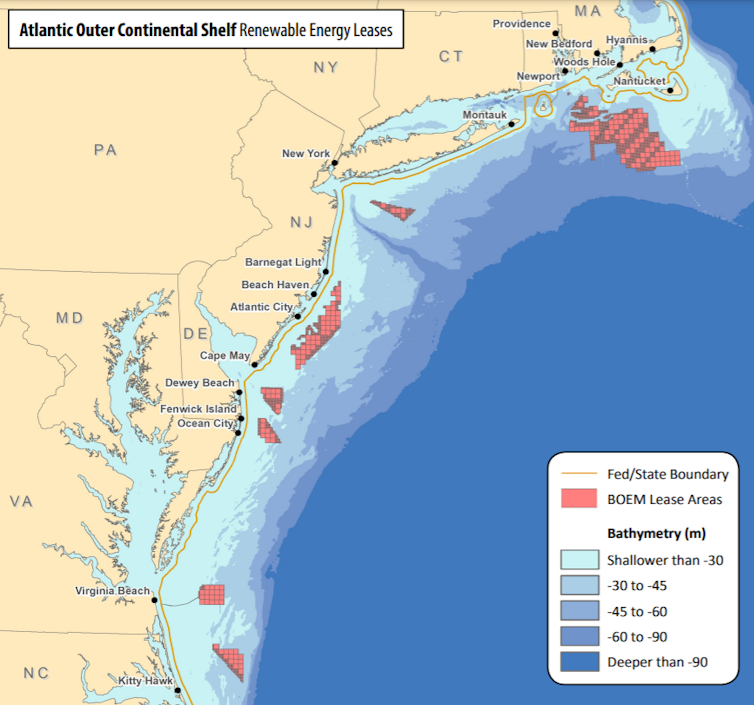

Several wind farm developers already hold leases in prime locations off the Eastern Seaboard, suggesting plenty of interest.

As engineering professors leading the Energy Transition Initiative and Wind Energy Center at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, we have been closely watching the industry’s challenges and progress. The process could move quickly once permitting and approvals are on track, but there are still obstacles.

Why offshore wind plans stalled under Trump

Vineyard Wind had planned to begin construction in 2019, but a ruling by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management under the Trump administration stalled it. The ruling cast a shadow over other wind farm plans and hopes for an U.S. offshore wind industry.

The agency ruled that the developers needed to address what is called “cumulative impacts” – what the East Coast will look like when there are not one or two, but 20 or 40 large-scale wind farms. That part of the U.S. coast is ideal for wind power because of its wide, shallow shelf and proximity to cities that are looking for renewable electricity to reduce their climate impact.

Many researchers studying offshore wind, including some of our colleagues, urge planners to take this perspective.

But thinking carefully about a far future with several wind farms does not justify blocking the first utility-scale wind farm now. That first large wind farm will be an opportunity to learn, including about how wind turbines will interact with marine ecosystems. Right now there is almost no data on the impacts of offshore wind on the region’s marine wildlife. The knowledge gained will be invaluable in moving forward responsibly.

Is fast-tracking federal approvals enough?

Speeding up federal approvals for offshore wind farms is an important first step, but those aren’t the only hurdles for offshore wind farm developers.

A large number of state environmental and coastal agencies also must approve offshore wind farm plans, and the communities where cables come ashore have a say.

Many of the Northeastern states, including Massachusetts, have their own offshore wind energy goals, so they’re likely to support wind farms. But some wealthy communities and the fishing industry have pushed back on wind power in the past. Vineyard Wind’s developers worked with community groups and fishermen from the region and agreed to compensate them for potential revenue losses.

The federal approval process, even fast-tracked, is also time-consuming. The government conducts reviews and requires site assessment plans, including geological, environmental and hazard surveys. From planning to construction, the entire process can take five to six years or more.

Is the US ready to build offshore turbines?

Some other big questions revolve around construction.

Under a 1920 law known as the Jones Act, only U.S.-registered vessels operated by U.S. citizens or permanent residents can move cargo between U.S. ports. In December 2020, Congress made clear that this law applies to wind turbine construction, too.

When companies build offshore wind turbines today, they use special vessels for the installation of the most common offshore turbine designs. The U.S. doesn’t have any of these vessels yet, and the Jones Act makes it difficult to rely on vessels from Europe to do the job. There is promise, though: The first U.S.-made version of this vessel is being built in Texas right now. That’s one – the country will need several to meet the new goal.

A thriving wind power industry will also need ports for storing and deploying the long turbine blades, plus a trained workforce for construction and turbine maintenance.

A few coastal states have a head start on this. Massachusetts started laying the groundwork early and already has a port terminal in New Bedford to support the construction and deployment of future offshore wind projects. New Jersey recently announced a plan for a new offshore wind port that will start construction in 2022, and Delaware has been considering one.

States are also investing in training. New York state announced a US$20 million offshore wind training institute in January 2021 with the goal of training 2,500 workers. The Biden administration envisions 44,000 people employed in offshore wind by 2030, and many more in communities connected to offshore wind power activity.

Costs and benefits of offshore wind

In Europe, where many governments have reduced regulatory risks to the industry, the cost of offshore wind energy has come down much faster than experts expected, to around $50 per megawatt-hour. If the Biden administration’s new approach allows U.S. wind farms to achieve costs like this, then offshore wind, with its proximity to large urban centers on the East Coast, will be competitive.

It’s also important to recognize other benefits. Every year of delay for a large-scale wind farm costs the U.S. hundreds of millions of dollars in climate benefits. The Biden administration calculates that its new wind power goal would avoid 78 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, roughly equivalent to taking 17 million cars off the road for a year.

Erin Baker, Professor of Industrial Engineering Applied to Energy Policy, University of Massachusetts Amherst and Matthew Lackner, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, University of Massachusetts Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.