Marjorie Hershey, Indiana University

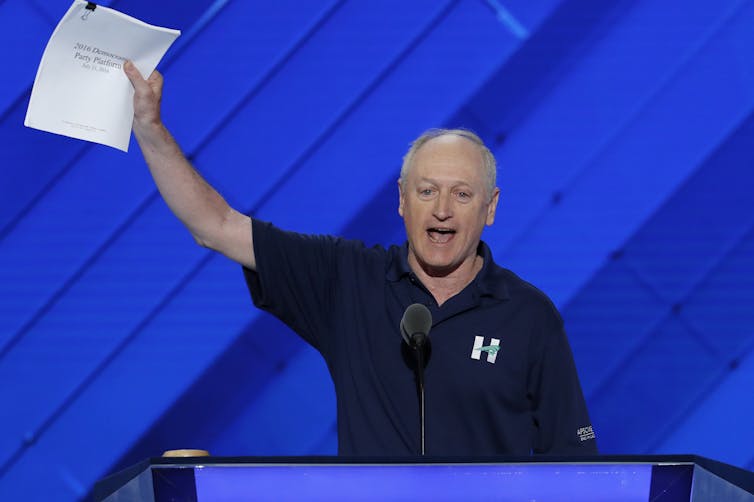

Political parties’ platforms – their statements of where they stand on issues – get little respect. President Donald Trump mused recently that he might shrink his party’s platform from 66 pages in 2016 to a single page in 2020. Even as far back as 1996, Republican presidential candidate Bob Dole claimed he had never read his party’s platform. Nor do Democratic Party platforms – such as the draft released July 22 – usually make the best-seller list.

If Trump wants to slash it, and Dole didn’t even read it, why should you care about a party’s platform? As a scholar of U.S. party politics, I have seen that party platforms are a vital clue about which groups hold real power in the two major national parties. When they are formally published after the parties’ conventions in August, they’ll also help you predict what the national government will actually do during the next four years.

Where does the platform come from?

Each national party has a platform-writing committee, composed of major party figures and representatives of interest groups closely linked with the party. They do their work in the spring and summer prior to the presidential conventions.

When there’s a first-term president, his or her party’s committee gets its direction from the White House; presidents don’t want to run for reelection on a platform other than their own. This year, the Republican platform is very much under the control of Donald Trump and his closest advisers.

For parties challenging a sitting president – such as the Democrats in 2020 – the platform committee holds hearings around the nation, in person and online, to hear from the public. In reality, those who testify are almost always leaders of interest groups. The party’s presidential nominee will also have great influence over its contents.

Writers of party platforms must combine the stirring – though very abstract – values that brought supporters to the party with the specifics desired by the party’s allied interest groups as the price of their loyalty.

This means simultaneously touting rhetorical key points such as strong national defense, fair treatment of all people or a great educational system, while making particular promises, such as pledges to nominate right-wing judges, ban specific policing methods or reduce particular emissions that cause climate change. The strongest party factions can get their goals written directly into the text of the party platform.

As a result, platform writers have to navigate the tension between candidates’ desire for a broad appeal to voters and interest groups’ insistence on explicit commitments to their goals. Typically, most of the platform’s language involves stirring appeals to the broader electorate. The rest is a laundry list of specific promises to organized groups.

Once it’s written, the platform is adopted by the party’s quadrennial national convention. In times past, fierce debate ensued over some platform elements, such as abortion. Now, the parties are so polarized, and the national conventions have become such a public display of unity and enthusiasm, that they try to avoid debate about the platform.

What happens then?

The party leadership can’t do anything to enforce its platform – and can’t even expel candidates who reject or only weakly support the platform. That’s because party leaders don’t choose the party’s candidates; the voters do, in primary elections, and voters don’t necessarily heed the advice of national party leaders.

The classic example of this is Rep. Phil Gramm, elected by voters in his Texas House district as a Democrat in 1978. Gramm sided with Republican House members to support President Ronald Reagan’s policies, and his Democratic colleagues punished him by taking away his seat on the prized House Budget Committee. Undaunted, Gramm returned to his district, and ran for his old seat as a Republican. He won. The fact that Gramm had been elected as a Democrat but rejected a key plank in the Democratic national platform apparently didn’t bother his voters at all.

There are even times a national party would rather that its candidate in a particular district not support the party’s platform. For instance, if Democratic voters in a swing congressional district have chosen to nominate a candidate who is pro-life, then that’s probably the type of Democrat most likely to win in that district. It wouldn’t benefit national party leaders to fight for a pro-choice Democratic candidate who would likely lose that district to a Republican.

Signals of coming action

Platforms may not bind elected officials, and they may go unread by almost everybody. Yet they do have meaning. Those who do read them can make a good guess about how a party’s elected officials will behave in office. Researchers find that when a party controls Congress and the White House, its spending priorities reflect issues emphasized in its platform most of the time. Most presidents make some effort to carry out their campaign promises; when they fail, at least until 2017, it’s normally been due to congressional opposition.

Changes in the platform are often significant indicators of change in the party. When the 1980 Republican platform dropped the party’s longstanding commitment to the Equal Rights Amendment and adopted strong anti-abortion language, that was clear evidence of the shift toward right-wing conservatism that now characterizes the Republican Party.

So you may never read a party platform, but don’t dismiss it as fluff; at least since World War II, it can tell you a lot about how the party will spend your tax dollars if it wins power.

Marjorie Hershey, Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.