Hamza Mudassir, Cambridge Judge Business School

Arm, the Cambridge-based microchip designer is a British tech success story. The firm designs software and semiconductors that are used in a multitude of consumer favourites, including Apple and Samsung smartphones, Nintendo consoles and many more. Its chip designs are increasingly used in the growing Internet of Things industry.

Much of Arm’s success comes from its neutrality, as it doesn’t compete with any of the companies it licenses its designs to. But there are fears this could all change. Arm’s owners, Softbank have announced a deal with tech giant Nvidia worth up to US$40 billion (£31 billion). A closer look at Arm’s success reveals why the tech industry is stunned by the news and why it poses potential problems for Arm going forward.

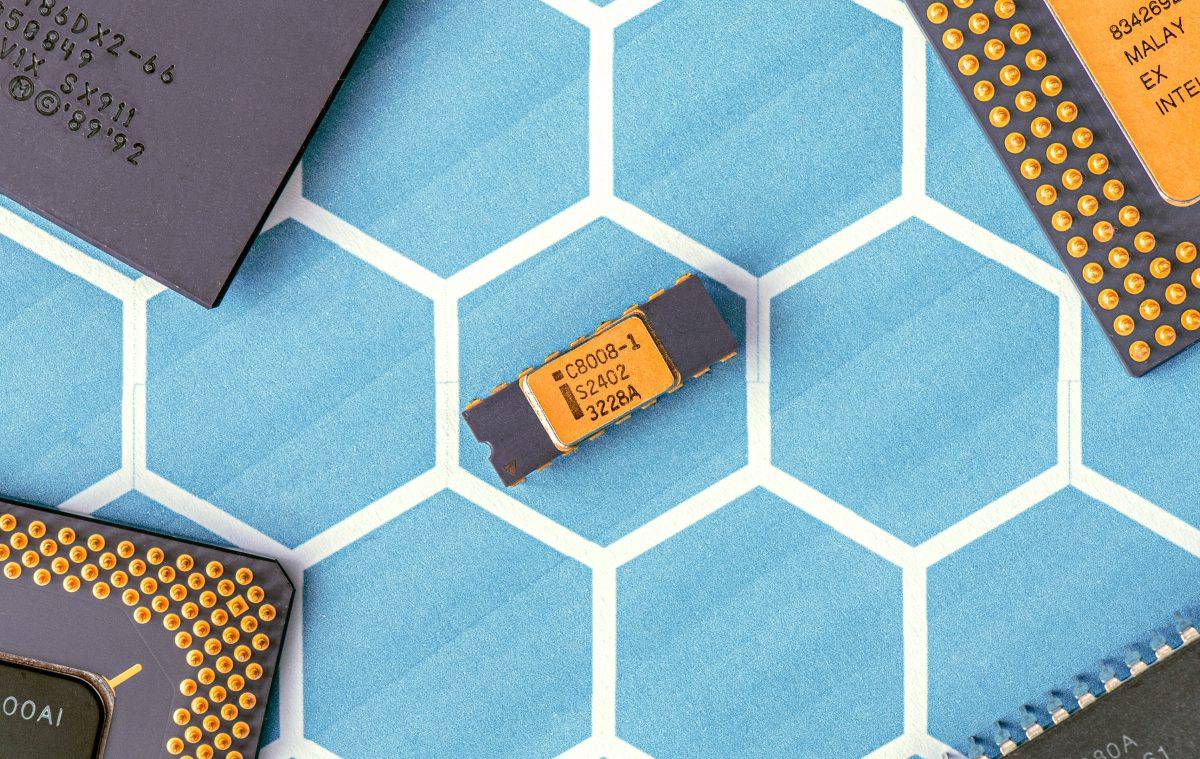

Arm defied the traditional notion of how a technology company competes in the global market place. To begin with, it does not manufacture any of its products. This is in sharp contrast to competitors Intel and AMD, who spend a lot of time, money and effort in manufacturing and marketing the microchips that they design. Instead, Arm licenses its patented designs to customers who can then easily modify, manufacture and market microchips around them.

Further, Arm has been a pioneer in building an ecosystem around itself, which currently consists of thousands of partners, vendors and manufacturers. This is a collaborative ecosystem, where many of Arm’s customers and partners have built their business models around Arm’s designs, secure in the knowledge that it is not a competitor.

The Switzerland of semiconductors

Arm’s model of collaborating instead of competing has resulted in a 90% share of the smartphone market alongside a reach that greatly exceeds that of rivals Intel and AMD. It is one of a handful of firms in the world that have successfully scaled a multibillion-dollar business built solely around research and development (R&D).

Arm co-founder Hermann Hauser describes the company as “the Switzerland of the semiconductor industry” because of this neutral approach. With this ethos holding strong for 30 years, thousands of companies have pegged their products to Arm’s R&D efforts.

This is in stark contrast to how the tech industry usually works. R&D investment is normally used as a tool to beat competitors, and it is quite common for large tech firms to compete fiercely with their own partners and customers. For example, Microsoft builds laptops and tablets that compete with many of the companies it sells its software to. Similarly, Google sells its Android software to other smartphone makers, while also competing with these customers with its Pixel phones.

Arm’s acquisition by Nvidia puts its Switzerland position at an obvious risk. Hauser said as much to the Guardian newspaper: “It is very much in Nvidia’s interest to kill Arm.”

Nvidia has promised to keep the Arm brand, maintain its neutrality and continue licensing its chip designs to customers. But many clients are concerned, with none of Arm’s big customers publicly backing the deal.

Nvidia is a US-based chip maker. It is the market leader in graphics processing units (GPUs), which power high-fidelity video games and increasingly handle data-intensive machine learning tasks. Leaps in microchip designs is one of the main ways it competes in its industry.

If this acquisition completes as planned, Nvidia would have gained a treasure trove of IP and patents that give it unparalleled power in the industry. Arm’s customers fear that they will become second-class citizens, with Nvidia first in line to its innovative new chip designs.

Another dimension to this deal is the fact that Nvidia is taking over Arm in the middle of the US-China trade war. This could put pressure on Arm’s China business, which represents about 20% of its revenues. In fact, in 2018, Arm divested its majority ownership in its China operations to give peace of mind to Beijing, which was increasingly worried about its dependence on foreign designed microchips. Such bold moves seem unlikely under Nvidia.

The deal will take up to 18 months to go through, as both Nvidia and Arm will have to get formal approval from competition commissions in the US, China, Europe and other major markets to proceed. But Nvidia’s assurances that it will keep Arm in Cambridge and expand its chip research there should go a long way toward assuage the British government at least.

In terms of Arm giving up its neutrality, research shows that mergers and acquisitions of this size can change acquiring companies as much as the targets they acquire. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has alluded to his plans to sell Nvidia’s GPU designs to Arm’s clients as part of a bundled offering. He also consistently speaks about his admiration of Arm’s unique place in the microchip ecosystem, and says he has no intentions to disrupt it.

Perhaps Arm will make Nvidia more neutral rather than the other way around. We will find out soon enough.

Hamza Mudassir, Visiting Fellow in Strategy, Cambridge Judge Business School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.