Lee Towers, University of Brighton

Many of the UK government’s flagship policies for the low-carbon transition are funded through people’s energy bills. On top of their energy use, every home in the country is paying extra on their bill to cover the cost of retrofitting programmes to increase the energy efficiency of homes, help for those in fuel poverty and subsidies for renewable generation. All of these costs are added to energy bills at a flat rate.

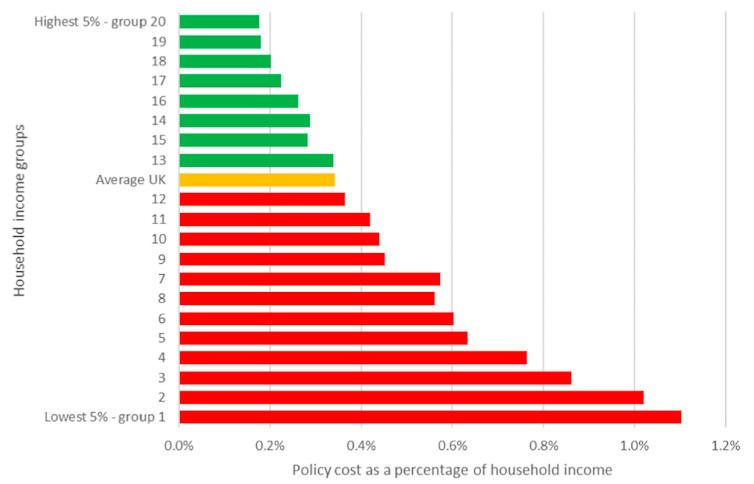

According to a 2015 report, this means, in practice, that those on the lowest incomes pay a six times higher share of their income for the transition than the highest income group, who also happen to have the highest CO₂ emissions on average.

Through energy bills, people in the lowest income groups effectively self-fund their own fuel poverty support, including measures like the warm home discount – a one-off winter payment of £140 (US$195) towards energy bills – while also paying towards measures that mainly benefit higher income groups, like subsidies for rooftop solar panels.

Academic Brenda Boardman warned about this problem in the 1990s. Not only is this not a fair way to fund the national effort to decarbonise the UK’s energy system, but that same unfairness is slowing the speed and reducing the motivation for a transition in the first place.

The big fix

The UK’s energy market is dominated by six multinational corporations. On the website of Ofgem, the energy regulator, a page documents the multiple infractions of these companies, known as the Big Six, from their treatment of vulnerable customers to their failure to fulfil obligations to reduce the carbon intensity of their gas and electricity.

Ofgem’s answer is a voluntary redress scheme which companies under investigation pay into. This often funds programmes which advise vulnerable customers, such as the chronically ill, on how to navigate an (often intentionally) bewildering energy market. Npower paid a record fine in 2015 of £26 million. The total number of fines and redress payments made in 2020 reached £71.3 million.

Had this money been spent directly on low-cost renewable generation, 57 megawatts of wind energy could have been installed, enough to power around 40,000 homes annually.

These six companies made profits of nearly £2 billion in 2015 from their standard tariffs. People are often placed on these automatically and tend to remain on them, with only the most nimble customers (around 30% in 2016) switching. The government noted that those least likely to switch to cheaper tariffs earn less than £18,000 a year, are aged 65 and over, with a disability, or live in social housing or the private rented sector. As a result, a significant proportion of these profits are extracted from those least able to pay.

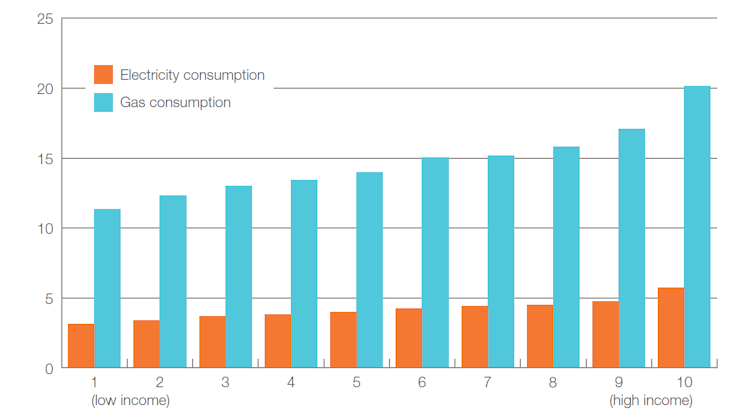

In fact, many people living in private rentals and social housing (20% and 17% of the population respectively) are effectively excluded from the choice of installing the solar panels and electric vehicle charging points their energy bills finance, because such freedoms tend to depend on home ownership.

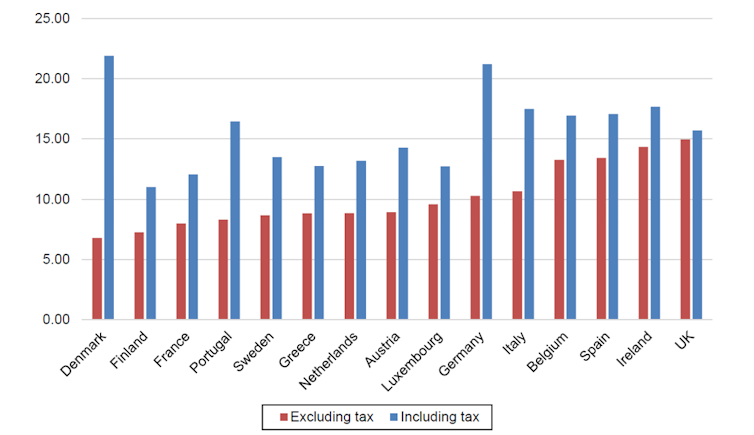

UK consumers also pay some of the highest pre-tax rates for electricity in Europe, and energy costs in general are higher than they should be considering falling gas prices since 2014 and more efficient boilers and smart meters. Meanwhile, the third of the bill which pays for the maintenance and environmental upgrade of energy infrastructure is taken at the same rate from billionaires as it is from those on Universal Credit. People without solar panels will continue paying for the essential network changes that incorporate the growing amount of renewable energy, and those who cannot afford to swap their fossil fuel burning car for an electric vehicle could end up having to travel further and emit more to get fuel, as retailers cease supplying or close their facilities.

While consumers fund measures which cut emissions from the UK’s energy system through bills, government policies effectively subsidise fossil fuels, mostly through forgone tax revenue. These UK subsidies result in effective investment in fossil fuel production of €11.6 billion a year, compared to the €7.76 billion invested in renewables. In this situation, the renewables consumers fund are more likely to add to the energy generated by fossil fuels, rather than replace it.

At the same time, renewable subsidies like the feed-in-tariff, which paid people for the excess energy they generated with solar panels, have been axed. This makes it harder for people to pay to install solar power at home. Clearly, the transition to low-carbon energy could be quicker if government policy didn’t work against the best intentions of the public.

And the public are aware. One study in 2019 found widespread misgivings about excessive profits, a lack of transparency and close ties between the government and big energy companies. If people don’t trust the institutions tasked with overseeing the end of the fossil fuel era, how will they be persuaded to make the necessary changes to their own lives?

Lee Towers, PhD Candidate in Energy and Politics, University of Brighton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.