Frank Jotzo, Australian National University and Mousami Prasad, Australian National University

Much has been made of the COVID-19 lockdown cutting global carbon emissions. Energy use has fallen over recent months as the pandemic keeps millions of people confined to their homes, and businesses closed in many countries. Projections suggest global emissions could be around 5% lower in 2020 than last year.

What about Australia? Here we’ve seen sizeable reductions in electricity sector emissions, but mostly from the sustained expansion in solar and wind power rather than the lockdown.

That is good news. It means our electricity sector emissions will not bounce back once COVID-19 restrictions are lifted, as they might in other parts of the world.

But on the other hand, a prolonged recession could cloud the outlook for new investments in the power sector, including renewables.

What’s clear right now is this: COVID-19 restrictions matter far less to Australia’s power sector emissions this year than the shift away from coal and towards renewables.

Small fall in electricity demand

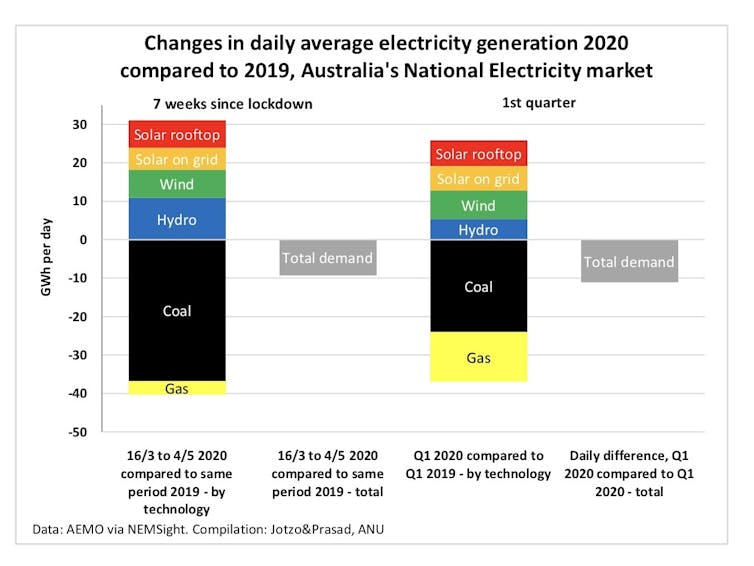

We examined Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) in the seven weeks from March 16 (when national restrictions came into force) to May 4 this year. We compared the results to the same period in 2019.

The NEM covers all states and territories except Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Total electricity demand was 3% lower during the first seven weeks of the lockdown, compared with the same period in 2019. About 2% of this was due to an actual fall in electricity use. The rest was due to extra rooftop solar panels installed since May 2019 which lowered demand on the grid.

Some of the 2% reduction may be due to cooler weather this autumn, leading to lower air conditioning use.

So while COVID-19 restrictions have hammered the economy in recent weeks, they haven’t had a big effect on electricity use. Most industrial and business power use has continued uninterrupted. Most office buildings have not fully shut down, although many people are working from home and use more electricity there.

A hefty drop in emissions

Despite the modest fall in electricity demand in the first seven weeks of lockdown, emissions fell substantially – by 8.5%. Comparing the first quarter of 2020 and 2019, emissions fell by 7%.

This is primarily because more renewable energy is now supplying the grid. Output from solar farms increased by 55% and from wind parks by 19% compared with the first quarter of 2019, reflecting massive amounts of new installed capacity coming online. Output from hydroelectricity increased by 18%, likely reflecting higher rainfall.

More renewables supply combined with falling demand means less output from fossil fuel power plants. Coal plant output fell 9% compared to the same period in 2019, entirely due to lower output by black coal plants in New South Wales and Queensland. Gas fired power output fell by 8%.

Electricity prices plunge

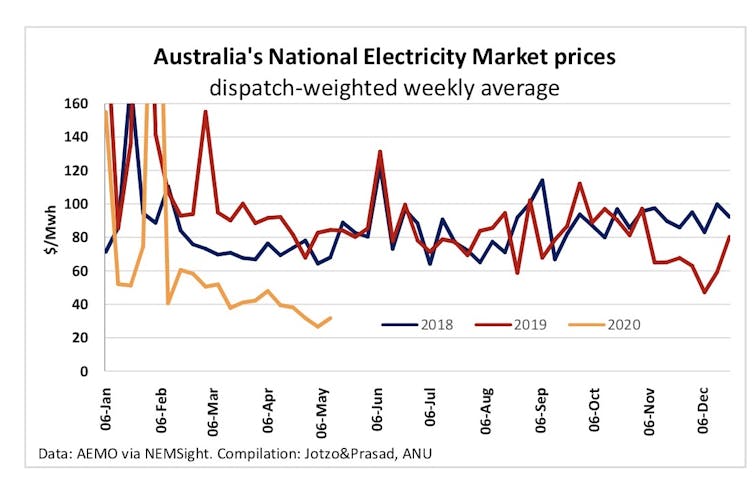

Meanwhile, wholesale prices in the NEM have fallen dramatically. The average price was 60% lower in the seven weeks since March 16 compared with the same period in 2019. A marked reduction in prices was evident from November 2019.

Why? One reason is that prices for natural gas are much lower and hence gas-fired power stations can make lower bids for electricity. Gas prices fell through much of 2019, and dropped further in the first quarter of 2020, associated with the pandemic-induced economic downturn. Gas plants often set the prices for everyone in the market, so this has a big effect on the market overall.

Also, coal and hydropower plants lowered their bids in this more competitive environment.

The outlook for wholesale prices remains flat. Gas prices seem unlikely to rebound soon. More wind and solar power will come into the market and there is no underlying growth trend in electricity demand.

Relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions is unlikely to make a big difference. What may drive prices up once again is the next large coal plant closure. The last one to close was Victoria’s Hazelwood plant in 2017.

What does this mean for coal and renewables?

Low wholesale electricity prices are good for consumers – in particular industry, where the wholesale price is a bigger proportion of the total charges for electricity supply. On the flip side, they mean less money for power generators.

Across the National Electricity Market, revenue for generators was about A$160 million per week lower during the first seven weeks of lockdown compared to the same period in 2019.

This revenue fall makes coal plants less profitable, and makes life uncomfortable for plants with relatively high costs for fuel and maintenance. It’s likely to push older plants closer to closure.

Lower prices also make investment in new renewable power less attractive. In recent years, average wholesale prices were well above the typical lifetime average costs of producing electricity from newly built solar and wind parks. There is also uncertainty around how prices will be set in power markets in the future, and how congestion of power transmission lines will be managed.

Nevertheless, the longer term prospects for renewables in Australia remain very good. Solar and wind power are the cheapest of all new generation technologies producing power, and solar power is expected to become even cheaper. A new coal-fired power plant, if one was ever built, would have far higher costs per megawatt hour. Costs for a nuclear plant would be higher still.

The way forward

The numbers show Australia does not need a painful recession to drive carbon emissions down. It needs sustained investment in new, clean technology.

The better the Australian economy recovers, the more private businesses will invest in new energy supply. But if the world falls into a deep and lasting recession, and the Australian economy with it, then the prospects for private investment in new power plants will suffer.

In that case, governments may be well advised to invest public funds in clean energy, more so than they have in the past.

Frank Jotzo, Director, Centre for Climate and Energy Policy, Australian National University and Mousami Prasad, Research Fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.