Timothy Rich, Western Kentucky University

With the U.S. presidential election approaching, Americans face a daunting set of challenges as they prepare to vote.

Many voters fear the coronavirus will force them to risk their lives at the polls. Yes, voting by mailrepresents a safe alternative. But President Donald Trump opposes additional funding for the United States Postal Service, and the agency has warned 46 states that mail-in voters could be disenfranchised by delayed mail-in ballots.

Past presidential elections and recent caucuses provide even more cause for concern: Rickety voting systems risk changing election results.

When faced with potential problems at the polls, other countries invite international observers to help monitor elections. Just recently, Indonesia, Trinidad and Tobago and Montenegro have welcomed observers.

As a political science professor who writes about electoral politics and has observed elections in other countries, I’ve seen international observers promote faith and integrity in foreign elections.

Should an international organization monitor U.S. elections in November for fraud? The public seems to think so, even amid a pandemic.

International observers in US elections

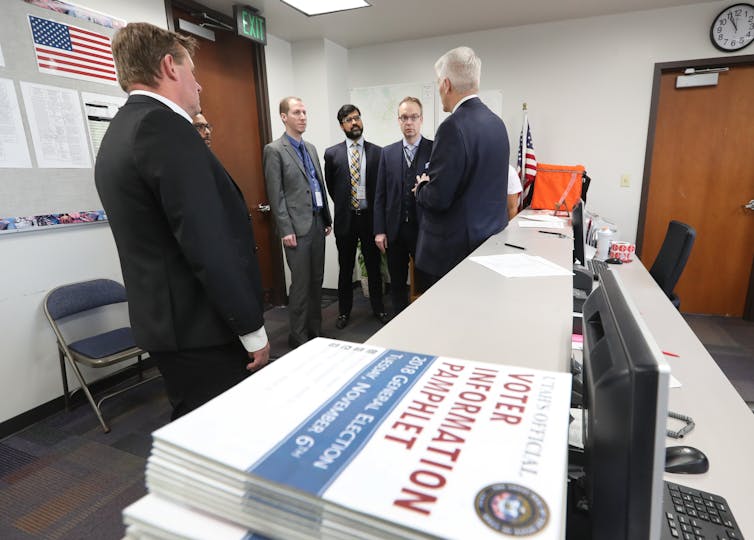

Election observers typically monitor the entire election process – not just Election Day. They examine candidate registration, observe the opening of polling stations and help count ballots, for example. But they do not have the power to stop questionable activity, only to report it.

The U.S. often supports international election monitoring in other countries through the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the Organization of American States. Election observers with these groups ensure electoral integrity and observe voting procedures for potential fraud.

International observers are no strangers to U.S. elections – they have monitored at least seven of them since 2002.

While the Republican and Democratic parties routinely recruit volunteers to monitor polls, election experts say it’s crucial that nonpartisan observers are present to ensure that observation does not devolve into voter intimidation.

Since U.S. elections are run by the states, states decide whether or not to permit international election observers. Several of them – California, Missouri, New Mexico and Washington, D.C. – have laws that allow for international observers. Additionally, Hawaii, North Dakota, South Dakota and Virginia have laws that allow election observers that could apply to international monitors.

But most other states do not welcome international observers. The practice is explicitly prohibited by statutes in Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas. All other states have been silent about international observation missions.

During the 2018 midterm elections, election officials in Kentucky, Louisiana, Montana, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and West Virginia refused to meet with international observers before the elections, according to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. That organization’s report said that Indiana officials, for example, informed its observation mission that observers “were not welcome in the state at all.”

Strong public support

Polls show that Americans are highly engaged in the November election – more so than in previous contests. But nearly half of them – Republicans and Democrats – expect to encounter problems at the polls. The coronavirus, malfunctioning voting machines and uncounted mail-in ballots represent just a few concerns.

While many states do not support election observers, evidence suggests the public largely does. With the International Public Opinion Lab at Western Kentucky University, we conducted a web survey in July of 1,027 Americans across the country. We asked them if their state should allow an international, independent organization to observe the November elections to identify potential fraud.

Our survey found broad public support for international election observers. More than 70% agreed or strongly agreed to allow observers, with Democrats more supportive than Republicans – 77.2% and 65.3%, respectively. We found similarly high support between those preferring Joe Biden, 74.2%, and those preferring Donald Trump, 65.2%.

We also found that respondents concerned about contracting COVID-19 were more likely to support election observers, regardless of party affiliation. This is perhaps linked to concerns about their ballots being counted if voters cannot go to the polls on election day and instead vote by mail.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic throws a wrench in the typical electoral observation mission. How will observers monitor large-scale mail-in voting? Will they monitor early voting or just polling stations on Election Day? Will states require international election observers to arrive early and quarantine?

Establishing credibility

COVID-19-related obstacles to voting – reduced number of polling stations and trouble recruiting polling station workers, as well as concerns about health risks from voting in person – will likely decrease trust in the 2020 election and potentially affect the results, according to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. That is why the group is calling for 500 international observers.

To encourage broad public confidence in the electoral process, state officials could invite international organizations to conduct observation missions, as many other countries do. This would help establish the credibility of election results and demonstrate a commitment to voter concerns.

In their invitation, state leaders could outline the safety measures they will take to minimize COVID-19 risks for voters, poll workers and election observers. They could also request clear guidance from international observers on how to monitor mail-in ballots and early voting.

The pandemic will challenge international observation missions, but ensuring fair elections in an essential component of American democracy. And international monitors have shown they can provide an effective means to reduce public concerns about fraud and voter suppression.

Maggie Sullivan and Mallory Treece Wagner contributed to this report and the original survey questions.

Timothy Rich, Associate Professor of Political Science, Western Kentucky University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.