If you ever make a stopover in Bangkok, Hong Kong, Singapore or Jakarta, visit a theatre – or temple – where they are showing Peking Opera. This is China’s most famous art-form, originating under the brilliant Sung Dynasty a thousand years ago rather like the Biblical enactments of mediaeval Europe.

During the nineteenth century, opera became formalised in the capital (since known as Beping or Beijing) where at least four major playhouses put on the best of 400 works. There are regional variations elsewhere in China, and the purest tradition may be on Taiwan which escaped the Cultural Revolution in the People’s Republic.

Yet wherever there are Chinese playgoers, mainland or overseas, the performance is much the same. Being so classical, it has stock characters; the plots are stereotyped; the scenery is simple and the props are symbolic.

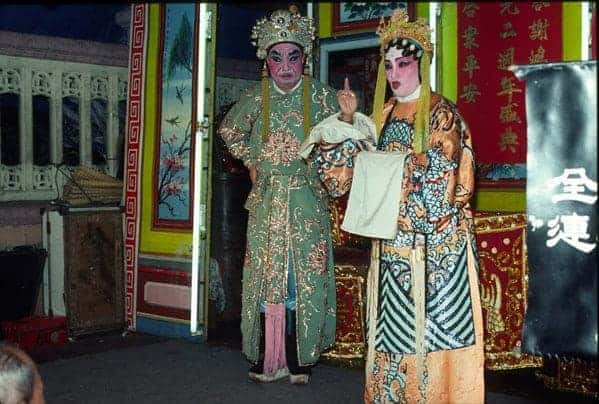

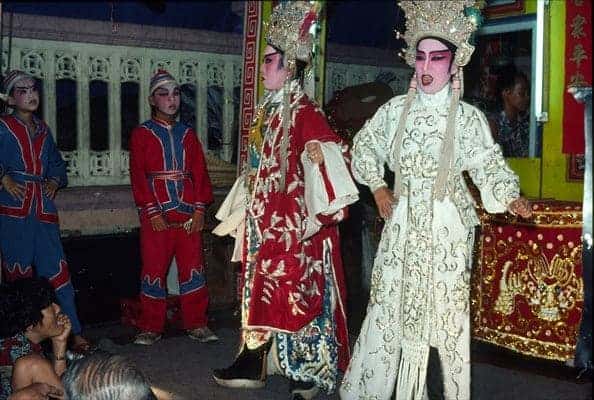

The main appeal for westerners lies in the exotic costumes, elaborate make-up and expansive gestures coupled with an orchestra, acrobatics and even martial arts. Even without the occasional synopsis in English, some research beforehand will help you follow the story.

Start with the properties and extras; they are basic – or not at all. The backdrop is a plain curtain with slits, left and right, or maybe a permanent piece of scenery, so choreography conveys going through the unseen doorways.

One table and two chairs might represent a bed or a bridge. That quartet waving flags is an army. A lackey with a lantern means nightfall. If a lady walks between two footmen holding pictures of wheels, she is riding a chariot.

Besides a male and female lead, the other main characters are a harlequin and a magician, but these roles have variants. The cast is clearly divided into goodies and baddies, not least because the plot will be about either military campaigns or strife and striving in society.

Peking Opera is far nearer Hollywood than the European stage in usually having a happy ending, as right triumphs over might. A typical title is The Faithful Harlot. A student, Wang, is cheated by the madame of Su San, with whom he is in love, so she gives him money to travel afar (he walks round the stage several times) for the imperial examinations.

Later on, Su San is lured to a supposed tryst with Wang, but is kidnapped to become a merchant’s concubine. The jealous wife gives her poisoned noodles which the merchant eats by mistake. Accused by his widow, Su San goes before a judge … who is none other than the successful Wang. He has the real murderess beheaded (not literally), acquits Su San – and makes an honest woman of her in a right regal wedding.

Either as scholar or lover, Wang need not clip on a false beard, of which there are 18 types for most other male parts. Most mature personages wear a black beard, while a long, white one obviously suggests old age, but purple is for a famous general and red for a bully. Mandarins are identified by three strands below the chin.

There is also a colour code for costumes with the fabrics’ ranging from cotton for coolies and clowns to silks and satins, systematically embroidered, for nobles and merchants. Most of the great and the good are in green, but the emperor himself wears a yellow robe, the only one displaying a rampant dragon, and the most extravagant of all head-dresses.

In Westerns, the good guy wears a white Stetson, but the Chinese make the villain pasty-faced. A florid complexion denotes an admired warlord, while bullies are blue in the face, and multi-coloured make-up betrays a rogue. Ladies with black cosmetics are not widowed, but defending their virtue.

If it takes hours to put on male make-up, it takes years to train Chinese operatic artists to make the intricate movements, especially with dangling sleeves, that form a recognised code for emotions ranging from fear to grief and from astonishment to embarrassment. The gamut goes way beyond the rolling eyes or sagging jaw of the silent cinema.

Chinese actors move feet, legs, hips, neck, arms, fingers and shoulders so that mime is part of the show. Yet this is opera, so there is a lot of singing – in a falsetto trill. The orchestra performs like the pianist in silent movies in order to signal such melodramatic moments as a looming attack, a time of terror, a grand entry…

The newcomer stands mute while the audience decodes headgear, make-up and costume, but certain notes warn: this man is a crook! Usually screened at stage left, the musicians have gongs and drums for martial music or strings and woodwinds in operas about civil society.

Last but not least, Peking Opera was into slapstick long before pantomimes, while the kung fu is more sophisticated than the gun-toting or bar-room brawl of a Western. The name covers several martial arts, and sword-play often suggests supernatural powers.

In all, it will be a magical and not too mystifying experience.