Recently, some of Europe’s most-visited cities have become surprisingly inhospitable to tourists. Barcelona residents have been openly hostile to visitors and officials are now cracking down on Airbnb rentals. Venice has been overrun with daytrippers and recently instituted tourist-only diversion routes. Dubrovnik has put a cap on the number of cruise ship passengers that can enter the city at any one time.

These destinations are suffering from what people in the travel industry call “overtourism.” The numbers speak for themselves. Europe was the most frequently visited region in the world in 2016, accounting for close to half of the 1.24 billion international tourist arrivals. Spain, a nation of 46.5 million people, welcomed a remarkable 75.3 million visitors in 2016. Croatia, population 4.2 million, saw more than triple the number of tourist arrivals.

Australia hasn’t yet experienced visitor numbers quite this large – there were just 8.24 million tourist arrivals in 2016 – but overtourism is becoming a concern here, as well.

What exactly is overtourism?

The awkward term overtourism describes a situation in which a tourism destination exceeds its carrying capacity – in physical and/or psychological terms. It results in a deterioration of the tourism experience for either visitors or locals, or both. If allowed to continue unchecked, overtourism can lead to serious consequences for popular destinations.

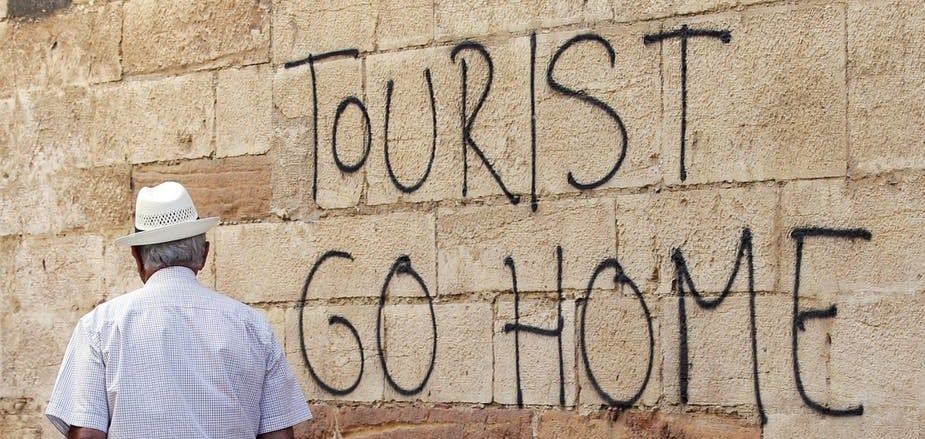

The situation has gotten so bad in certain locales in recent years, media outlets have started publishing lists of the “travel destinations you should avoid” and new terms like “anti-tourism” and “tourismphobia” are entering the travel industry lexicon. Tourist sites have even occasionally been targeted with violence, such as the string of attacks that took place in Spain last year.

The causes of overtourism vary according to the destination. Recently, the disruptive agents of the sharing economy, like Airbnb, have been blamed for bringing more tourists into the heart of communities instead of just tourist sites. Cheap travel and package holidays are enabling more people to take short city breaks and cruises, particularly in Europe. Social media also plays a role in popularising places like Myanmar, which go from being off-the-grid to “must-see” destinations overnight.

The shifting focus of governmental tourism agencies play a role in overtourism, as well. Many agencies are now almost exclusively marketing-focused and their singular goal is promoting growth. For instance, Tourism Australia’s “Tourism 2020” strategy is clearly growth-focused. Its goal is stated simply on the website – to achieve more than AU$115 billion in overnight spending by 2020 (up from AU$70 billion in 2009).

Sustainable tourism strategies, once heavily promoted in the 1990s and early 2000s, no longer seem to be as high a priority.

Is Australia really in danger of overtourism?

Australian tourism sites like Kangaroo Island aren’t seeing visitor numbers anywhere close to Venice and Barcelona just yet. However, poor tourism policies may still lead to a form of overtourism if locals perceive their quality of life is being damaged by tourists.

For instance, the 2011 Kangaroo Island Pro-Surf and Music Festival faced considerable community opposition for its proposal to bring 5,000 visitors to the small hamlet of Vivonne Bay (population 400). Recently published research examining the policy process indicated it was a push by tourism authorities to boost tourism on the island that led to the event being imposed on the community. The backlash was so severe, organisers abandoned plans to host the event again in subsequent years.

However, this hasn’t stopped other tourism development schemes from being proposed. And the state Economic Development Board has recommended doubling the numbers of tourists on the island by 2020.

Tasmania, too, has experienced a tourist backlash in recent years. Most recently, thousands came out to protest a proposed cable car for Mount Wellington near Hobart. With claims by critics that the cable car would draw upwards of 1 million tourists per year, one can readily see the seeds for overtourism.

Another site that could be in danger is the Great Barrier Reef. Agricultural run-off, climate change and a crown-of-thorns starfish outbreak are currently posing grave threats to the reef, which could spark a phenomenon known as “last-chance tourism”, – a rush to experience a place before it’s gone for good.

What can be done?

Most experts agree government regulations are key to addressing the threats from overtourism. Many cities, for instance, are following Barcelona’s lead to tighten restrictions on Airbnb. The Thai government is closing popular Maya Beach on Phi Phi Island for four months every year to allow the sea life to recover. Creatively, Copenhagen is promoting a tourism policy based on “localhood”:

A long-term vision that supports the inclusive co-creation of our future destination. A future destination where human relations are the focal point. Where locals and visitors not only co-exist, but interact around shared experiences of localhood. Where our global competitiveness is underpinned by our very own localhood. And where tourism growth is co-created responsibly across industries and geographies, between new and existing stakeholders, with localhood as our shared identity and common starting point.

And in New Zealand, the tourism board is actively promoting tourism visits outside of peak season. This is a good example of how government agencies can use “demarketing” strategies, or deflecting interest in places, to address rising tensions over tourism. Similarly, Majorca’s authorities have tried to rebrand it as a winter destination in an effort to reduce overcrowding in the peak season.

![]() With its “Tourism 2020” strategy, Australia is focused instead on growing its visitor numbers. The national and local tourism bodies should take a more sustainable and holistic approach to their tourism planning to reflect the values and desires of local communities. That will ensure visitor numbers remain in check and tourism remains an enjoyable experience – for tourists and residents alike.

With its “Tourism 2020” strategy, Australia is focused instead on growing its visitor numbers. The national and local tourism bodies should take a more sustainable and holistic approach to their tourism planning to reflect the values and desires of local communities. That will ensure visitor numbers remain in check and tourism remains an enjoyable experience – for tourists and residents alike.

_________________________________________

By Freya Higgins-Desbiolles, Senior Lecturer in Tourism Management, University of South Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

TOP IMAGE: Alberto Morante/EPA/The Conversation